Are Hurricanes Getting Stronger Or Not?

The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) maintains a subsite dedicated to the increasing risk of “more intense hurricanes that carry higher wind speeds and more precipitation as a result of global warming.” In their view, hurricanes are not getting more frequent, just more destructive.

A paper from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) on the most destructive hurricanes in U.S. history appears to support this theory. It lists the most destructive hurricanes since the 1930s, showing a consistent increase in the damages caused by major hurricanes even after adjusting for inflation.

According to the paper, in the 2010s hurricanes caused over $521.8 billion in damage (in 2013 dollars), over 10 times the cost in the 1980s ($39.2 billion) even as the total number of hurricanes has been in decline. Of the ten category 4 hurricanes in the data, seven of them happened in the last twenty years.

While major hurricanes like Katrina and Andrew have certainly reaped catastrophic damage to the U.S. in recent years, the average rating for hurricanes hasn’t changed much. And a similar report from the National Weather Service (NWS) on the NOAA site shows the strength of the average hurricane to be in decline, going from 3.4 in the 1920s to 3.1 in 2000s.

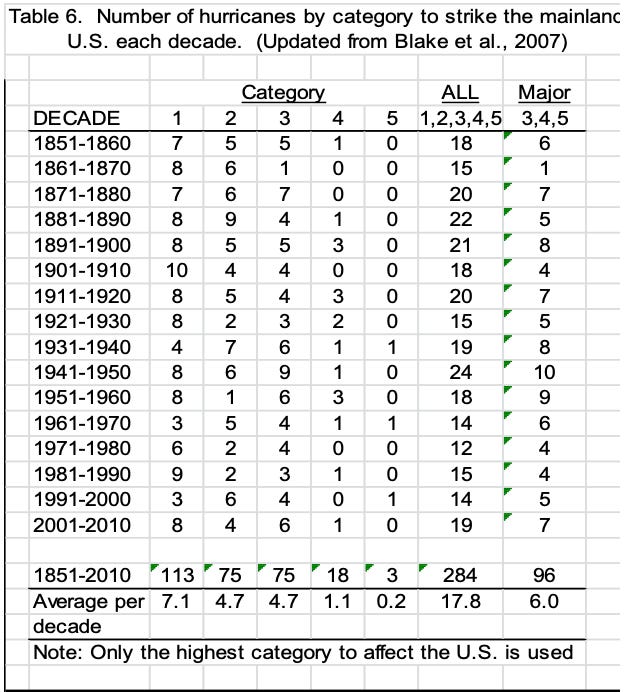

That report shows a breakdown by decade that lists the 1940s as the decade with largest number of major hurricanes (category 3, 4, or 5) and the largest number of total hurricanes to have hit the mainland.

Hurricanes are categorized by the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which is based on their maximum sustained wind speed. The scale starts with category 1 storms with winds at 64 to 82 knots and goes up to a category 5 where winds are 137 knots or higher. Anything below 64 knots is a tropical storm. Both tropical storms and hurricanes are subcategories of tropical cyclones.

According to NOAA’s Hurricane Database (HURDAT), the number of tropical storms has been steadily increasing in both the Atlantic and the Northeast and North Central Pacific Ocean.

But the percentage of those with higher wind speeds classified as hurricanes hasn’t substantially increased since the 1970s when satellite observance of hurricanes improved.

The total number of tropical storms in the Atlantic with winds over 64 knots was about the same in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s as the 1950s and 1960s. And the average maximum wind speed for those storms has been relatively consistent.

Effectively, the HURDAT data appears to say the opposite of the UCS—that tropical storms are becoming more frequent but not necessarily stronger.

HURDAT data also doesn’t provide details on maximum wind speeds for storms before 2004, but based on the data it does have it doesn’t show any significant increase in maximum wind speed.

Since 2000, there have certainly been major hurricanes outside of the norm. While hurricane Katrina was the most financially destructive and the third lowest pressure on record, hurricanes Ian, Michael, Isabella, and Irma were all category 5 storms with high wind speeds in the Atlantic since 2000 that didn’t cause as much destruction on land.

According to the NWS report, there are plenty of hurricanes prior to 2000 that rank higher in terms of maximum wind speed: hurricanes Andrew (1992, 145 knots), Indianola (1886, 135 knots), and Last Island (1856, 130 knots).

IBTrACS Data

Another NOAA hurricane data set is the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS). IBTrACS attempts to merge all current global storm data from various agencies into one unified dataset for all purposes.

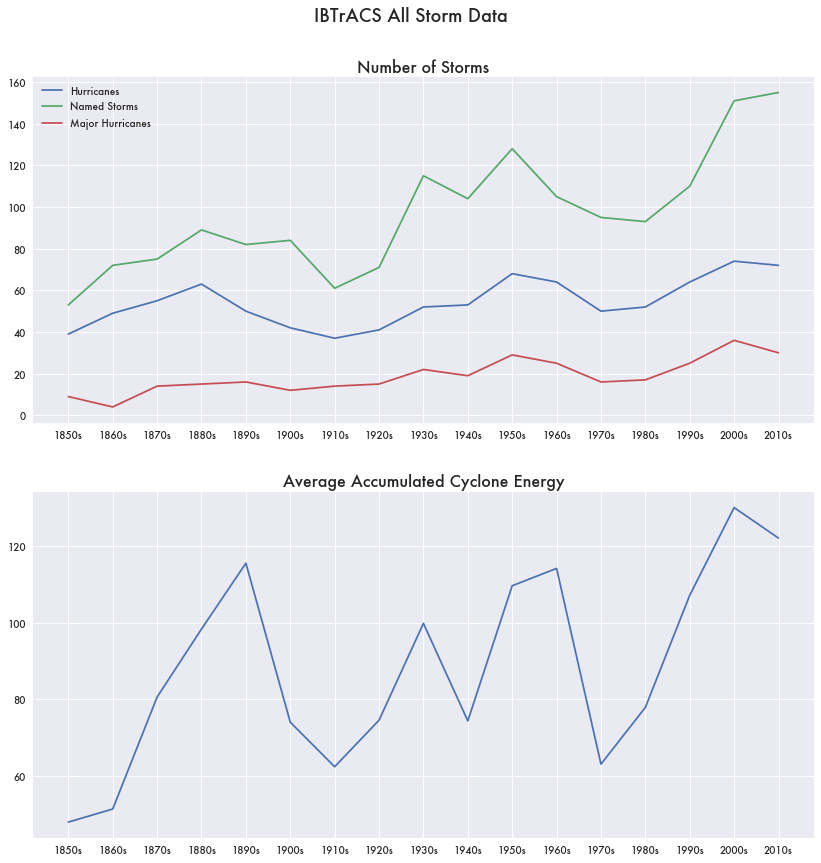

That data also appears to show a growing number of storms of all sizes across most decades in the last 170 years contrary to the UCS statements. But it supports the UCS by showing a growing trend of higher average accumulated cyclone energy (ACE)—a metric of storm wind speeds integrated over the life of the storm—and therefore more intense storms. This is opposite to the HURDAT data showing no real consistent growth in storm wind speeds.

The Large Uncertainties in Measuring Storms

Even with modern satellite technology and NOAA’s best track approach to storm data, there are numerous caveats to storm metrics. While tracking improved immensely with the use of satellites in the 1960s and 1970s, it wasn’t until the advent of microwave imaging satellites in the 1990s that they could collect information without the distraction of cloud cover.

Prior to satellites, reporting was based on surface interactions from storms that hit the mainland, ships that got too close, or from airplane reconnaissance missions.

If wind speeds aren’t being measured directly, then they are estimated using various modeling techniques like the Dvorak method, which makes estimates using a storm’s vorticity, vertical wind shear, convection, and core temperature usually captured via satellite.

While the Dvorak method appears to be well established, error ranges on wind speeds even in the current era can still be between ±10 knots. Different agencies also count storms differently. Some include tropical depressions and sub-tropical storms while others don’t.

Re-Analysis of Older Storms

Because of the inaccuracies involved in measuring storms from the pre-satellite era, NOAA has worked to reanalyze storm data going back to 1851 through the Atlantic Hurricane Database Re-analysis Project. As a result, some storms have been removed from the data and others upgraded.