Businesses Spending Heavily in Missouri, West Virginia Attorney General Races

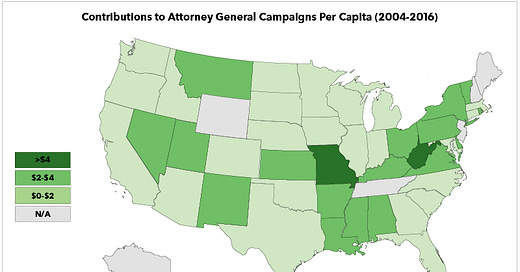

The most expensive attorneys general races in recent years have been in Missouri and West Virginia. On a per capita basis, money spent in those two states easily surpassed other races in more populous states like New York, Texas, and California.

Tort reform advocates said that the heavy spending there is a result of business groups trying to influence attorneys general races in states regularly known for personal injury lawsuits with questionable decisions and where campaign finance limits are few.

While spending by businesses was high in those two states, lawyers and lobbyists are by far the largest contributors to attorneys general races overall, and Jim Hood's campaigns in Missippi stand out for most money from lawyers and lobbyists on a per capita basis.

Lawyers and businesses donating to attorneys general that might appear in cases brought by attorneys general might be considered a conflict of interest, but campaign finance experts said that attorneys general do not currently have the same conflicts of interest standards as elected judges.

Conflicts of interest related to attorney generals have come under increased attention recently as New York attorney general Cyrus Vance dropped investigations against film producer Harvey Weinstein and members of President Donald Trump’s family while also receiving campaign contributions related to those being investigated.

Missouri’s Outsized Ranking

Despite its smaller population compared to California, New York, and Texas, Missouri was still the fourth most expensive state for attorneys general campaign spending in total and the number one most expensive on a per capita basis according to numbers from the National Institute of Money in State Politics.

West Virginia was second with over $5 spent on attorneys general races per person.

Attorneys general Eric Schneiderman (D) of New York, Greg Abbott (R) of Texas, Chris Koster (D) of Illinois, Kamala Harris (D) of California, and Jim Hood (D) of Mississippi represented one-fifth of the donations given to the top 100.

But on a per capita basis, it was West Virginia and Missouri who stood out from the rest.

The top four most expensive per capita campaigns were almost all from those two states: Douglas Reynolds (Dem.-WV), Andy Beshear (Dem.-KY), Josh Hawley (Rep.-MO), and Patrick Morrisey (Rep.-WV).

Missouri’s 2016 Race

In 2016, almost $22 million was contributed to the Show-Me state’s attorney general race.

Kurt Schaefer (Rep.-MO) brought in over $5 million on a failed primary bid alone, largely funded by conservative groups and businesses.

In that race, David Craig Humphreys, owner of Tamko Building Products, Inc. and his wife gave a total of $4.7 million to the campaign of Josh Hawley, which, by itself, was almost half of what Hawley brought in altogether ($10.3 million) and the largest single donation in the data.

Tamko is currently facing a class-action lawsuit over allegations it sold defective roofing shingles.

While Tamko was the largest single donor, conservative policy donors gave the bulk of the money—over $6.4 million worth—in Missouri’s 2016 race. That influx of money was double what conservative groups previously spent on any attorneys general race.

AG Spending and ‘Judicial Hellholes’

Darren McKinney with the Americans for Tort Reform Association (ATRA) attributed the high per-capita spending in places like Missouri and West Virginia as potentially related to abuse of personal injury lawsuits in those states.

McKinney described the influx of money to those states as being the result of the business community realizing that they could support candidates less likely to bring malicious state suits.

McKinney also called St. Louis, Missouri the number one ‘judicial hellhole’—a plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction that takes advantage of outside business “like small town speed traps”—because of recent personal injury lawsuits related to Johnson and Johnson’s talcum powder.

Page Faulk, senior vice president of legal reform initiatives with the Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform, also called Missouri and West Virginia’s legal climate ‘problematic’ because of the number of questionable verdicts coming out of St. Louis.

McKinney pointed to other jurisdictions with questionable verdicts, like South Carolina and Louisiana, but those states all have contribution limits.

Neither West Virginia nor Missouri had such limits in recent elections.

Lawyers Giving to Lawyers

Lawyers and lobbyists are by far the largest contributors to attorney general campaigns since 2004, according to numbers from the National Institute of Money in State Politics.

Lawyers' and lobbyists' influence in attorneys general races is over twice what it is for all races. For all races, they are the fourth-largest donor group behind party committees, self-funding candidates, and public sector unions.

But on a per capita basis, it was Jim Hood (D) in Mississippi raising the most money. His campaigns in 2007, 2011, and 2015 were the first, second, and eleventh most funded by lawyers and lobbyists respectively.

Their influence is significantly more for Democratic attorneys general, where they gave twice as much as to Republican ones.

DAGA’s Rankin said the difference between Democratic and Republican donations reflects a general trend of lawyers giving to Democratic candidates in all races to support consumer protections.

Rankin also appreciated the new focus on attorneys general races as they have “been off the radar for far too long.” Some states have seen dramatic increases in spending.

Law Firm Donations and Contingency Fee Contracts

Donations to state attorneys for contingency fee contracts—agreements for law firms to work with attorney generals on state suits to bring lawsuits in exchange for a percentage of any proceeds garnered from the suit—have been a contentious issue for some time.

Groups like the Association of Trial Lawyers and the Philadelphia Trial Lawyers Association as well as contingency fee law firms like Bailey Peavey Bailey gave hundreds of thousands in attorneys general races, sometimes spread across the country.

Compared to donations from large companies, donations from law firms were relatively small on a per donation basis. Although the numbers could be higher as the data does not detail when donations come from the employees of a law firm.

The Philadelphia Trial Lawyers Association was the biggest donor in that category, and they only gave $500,000 in total for all years, with other firms like Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check, LLP, Bailey Peavey Bailey, Ballard Spahr LLP, and the now defunct Dickstein Shapiro further below.

When it comes to how contingency fee arrangements are made, the Chamber of Commerce’s Faulk said that “there are significant concerns about conflicts of interest, use of state power for personal gain, and fairness in the judicial process.” with respect to how contingency fee arrangements are made.

ATRA's McKinney said that they have been pushing for transparency in contingency fee contracts for decades and 18 states now require transparency in transactions.

Company Donations and AG Lawsuits

Large companies that have been the target of lawsuits by state attorneys general—and might be the target of more—make up the largest donors to the tax-exempt 527 groups funding attorney general races—the Republican Attorneys General Association (RAGA) and its Democratic counterpart (DAGA)—according to numbers from Political Money Line.

These include pharmaceutical companies like Purdue Pharma and Pfizer; Living Essentials LLC, the maker of 5-Hour Energy drink; tobacco manufacturers Reynolds American and Altria Group; payday lender Ace Cash Express; and AT&T—each of which has recently been the defendant in a case before a state AG.

The list of top donors also includes groups eager to have state AGs bring lawsuits against the federal government.

For example, the National Education Association gave DAGA $275,000 as it supported a set of lawsuits by state AGs against the Department of Education’s repeal of the “Borrower Defense Rule.”

Bipartisan Giving

Some companies, like Purdue Pharma, Altria Group, Pfizer, and Anthem Inc. simultaneously gave to both DAGA and RAGA in 2016.

Sean Rankin, DAGA executive director, saidthat such across-the-aisle giving is nothing new.

“Attorney generals have historically had a different ethos about working together across the aisle that you don’t see in the Senate and other races. That animosity—or lack thereof—extends to donors to attorney general campaigns who are commonly more bipartisan,” he said.

AG Conflicts Dissimilar to Judges'

Tara Malloy, senior director of appellate litigation and strategy with the Campaign Legal Center, said that conflict of interest rules aren’t applied to attorneys general as they are to judges because "state prosecutors lie between the executive and the judicial."

Judicial elections have received increased scrutiny following the recent Caperton Supreme Court decision, which found that judges may have to recuse themselves from cases when campaign spending might affect due process in a case.

While there might be a potential conflict of interest in such donations to an attorney general, CLC’s Malloy said "there's no due process right to an impartial attorney general.”

She added that restrictions on bribery, graft, and using public office for personal gain already exist but they require evidence of a quid pro quo agreement between the donor and the attorney general.

Malloy believes there might be more nebulous conflicts of interest when a lawsuit could affect the donor's competition, but those cases would be difficult to prove.

Brad Smith, communications director with the pro-money in politics group Institute for Free Speech, said that corporate donations like this are less about potential bribery and more about supporting candidates that have similar beliefs.

“The vast majority of contributions are non-corrupting,” he added.

But to Paul Ryan, vice president of policy and litigation at Common Cause, attorneys general races are part of the larger conflict of interest issues that affect all political races and that even the appearance of corruption undermines the confidence of the public.

"The public wonders if they get a fair shake in court because attorneys general are fundraising from the private sector," he added.