California's FAIR Plan Didn't Really Collect Premiums

Because of heightened risks from fire in recent years and state policies restricting changes in insurance rates, numerous home insurers have left California, or substantially scaled back the number of policies they provide, in the last year, particularly in fire-prone areas of the state.

Because of ballot initiative Proposition 103 in 1988, insurers are required to gain approval from the state for any price hikes on their policies. While the state does grant rate hikes, it can take time and it’s not always by the amount that the insurance company had hoped for.

As private insurers offer fewer and fewer policies, more Californians have had to lean on the state’s FAIR plan—a state-provided insurance program as a lender of last resort. FAIR isn’t so much an insurance provider but a risk pool shared across private insurers and plan recipients. When catastrophe hits, insurers can simply pass on the financial burden to its ratepayers.

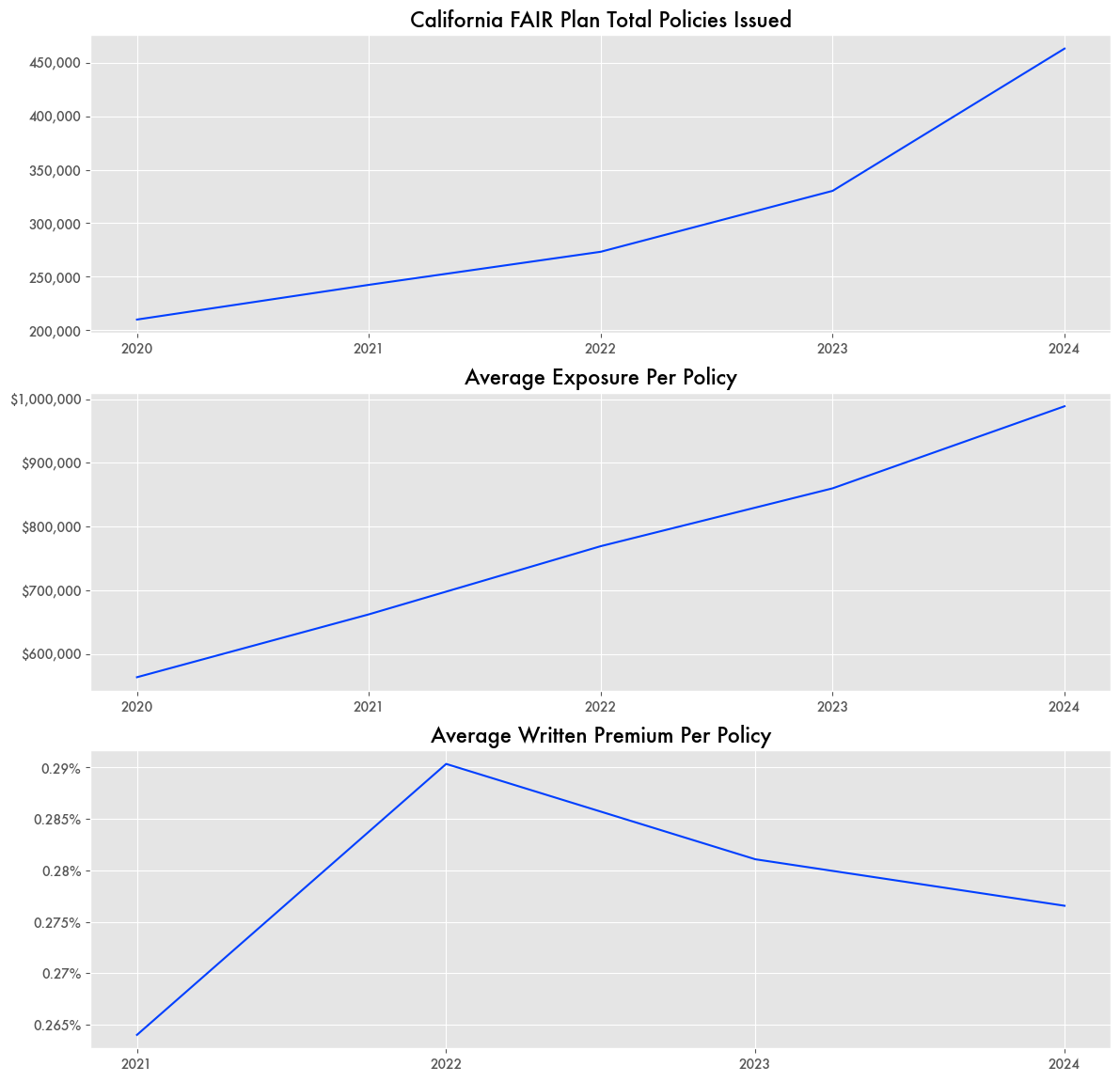

According to California Department of Insurance reports, the number of policies under the FAIR Plan have doubled since 2020. Total exposure of the plan quadrupled over that time and now stands at $455 billion. Plus, they are insuring more and more expensive houses. The average coverage is now at $1 million per policy. Previously it was near $600,000.

The number of policies in the Pacific Palisades—one of the areas hit hardest by the recent Los Angeles fire storm—quadrupled since 2020. Total exposure increased 117 percent in the last year alone and increased seven-fold since 2020. For the Valencia area of Santa Clarita it increased 345 percent just in the last year.

The California Department of Insurance knew full well the limitations of FAIR plans and that it could be a potential “hidden crisis.” They also described FAIR plans as “limited coverage at a higher cost”:

A major wildfire in one geographical area concentrated with FAIR Plan-insured properties could overwhelm the FAIR Plan’s reserves and its capacity to quickly and fully pay consumers’ claims.

The department proposed an update to the FAIR plan program in 2024, the Sustainable Insurance Strategy, that forced insurers who want to do business in the state to offer 85 percent of their housing policies in “wildfire distressed areas.” It would also force insurers to pay at least half the costs of losses rather than potentially zero.

But the recent L.A. fire has likely blown through any glimmer of FAIR’s loss reserves. Recent estimates put the cost of the fire to the FAIR plan at around $25 billion. Yet, a 2022 operational assessment of the FAIR plan listed total cash and short-term investments at only $148.6 million—a staggeringly low number considering they listed $1.27 billion in written premium in 2024.

But even $1.27 billion in potential annual revenue seems low considering the massive size of their exposure. With $455 billion in coverage in 2024, their premium-to-coverage ratio is .28 percent.

That is, for a house worth $300,000, the potential premium paid for fire insurance in a wildfire distressed area might be $830 a year. That is particularly cheap considering that most homeowners can pay over $1,000 a year for basic homeowner’s insurance, and fire insurance is regularly more expensive—1.25 times more according to the New York State Department of Financial Services. With the recent prevalence of fires in California and the high risk of repeated episodes, chances are it would be even more expensive.

And that is just “written premium”—what they might expect to receive but not actual revenue—so the plan’s actual cash flows could be even lower than that.