Cap and Trade Credits Largely Sent to Native Tribes, Alaska For Forest Management

Cap and trade is a market-based approach to mitigating the release of carbon and methane or other chemicals. In countries and states where it is implemented, companies are capped at the amount of discharged material they release and if they go over that limit they must purchase an equivalent offset through a trading market from a company that has earned negative emissions by capturing restricted material.

For example, petroleum refineries might be forced to buy carbon offsets from a company that does forest management or environmental mitigation. The costs of cap and trade are one of a number of reasons why California gas prices are consistently higher than every other state except Hawaii by $1 to $2 per gallon.

Cap and trade is the law of the land in much of Europe, but it’s only in a few places in the U.S.—mainly California, Oregon, and Washington in the West while some states in the Northeast have started making plans for cap and trade markets through the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

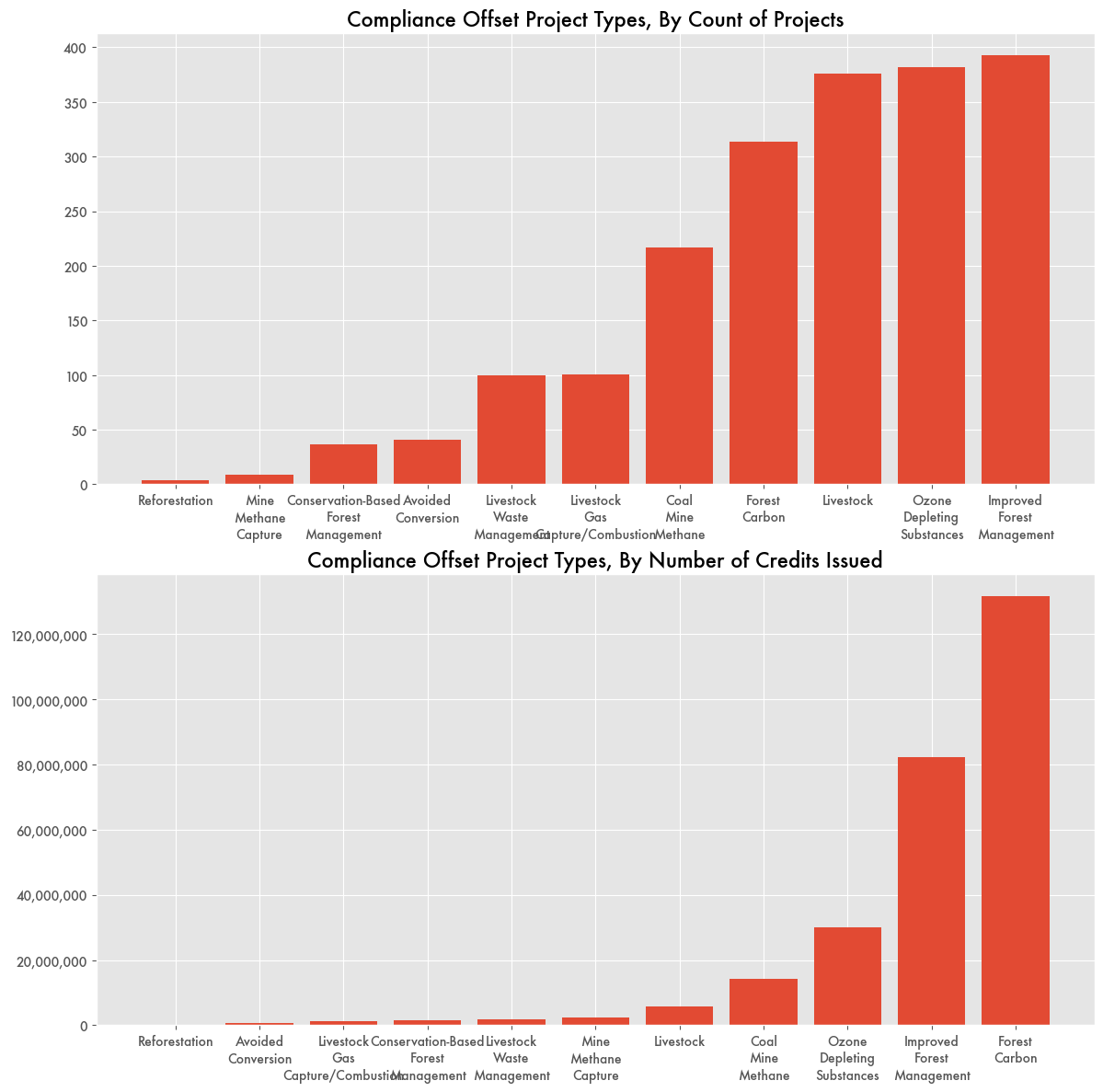

The California cap and trade market, which it shares with Quebec, is easily the largest in the U.S. The value of a credit varies with time and market fluctuations. For the California market it was once around $15/credit but now hovers around $40/credit. So for the 3.8 million in credits issued in 2024 alone based on data from the California Air Resources Board (CARB), that might equate to somewhere around $154 million spent on credits for things like forest management, livestock gas capture, mine methane capture, or removing ozone.

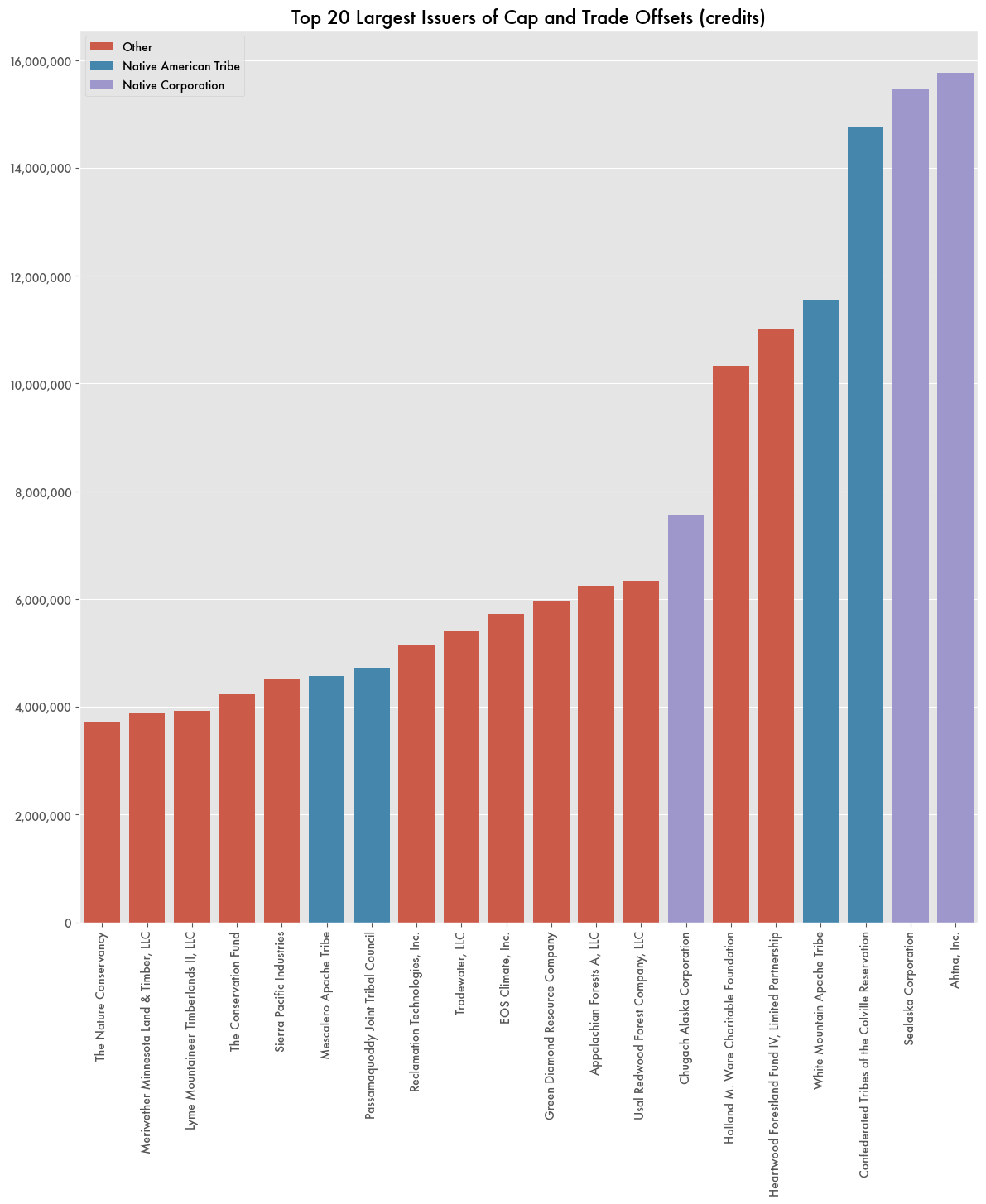

While many of the organizations that produce credits are environmental organizations like the Nature Conservancy, forestry companies, or various philanthropic funds, a full 31 percent were given to either native American tribes—like the confederated tribes of the Coleville Reservation or the White Mountain Apaches—or native American-owned companies like Ahtna, LLC or the Sealaska Corporation.

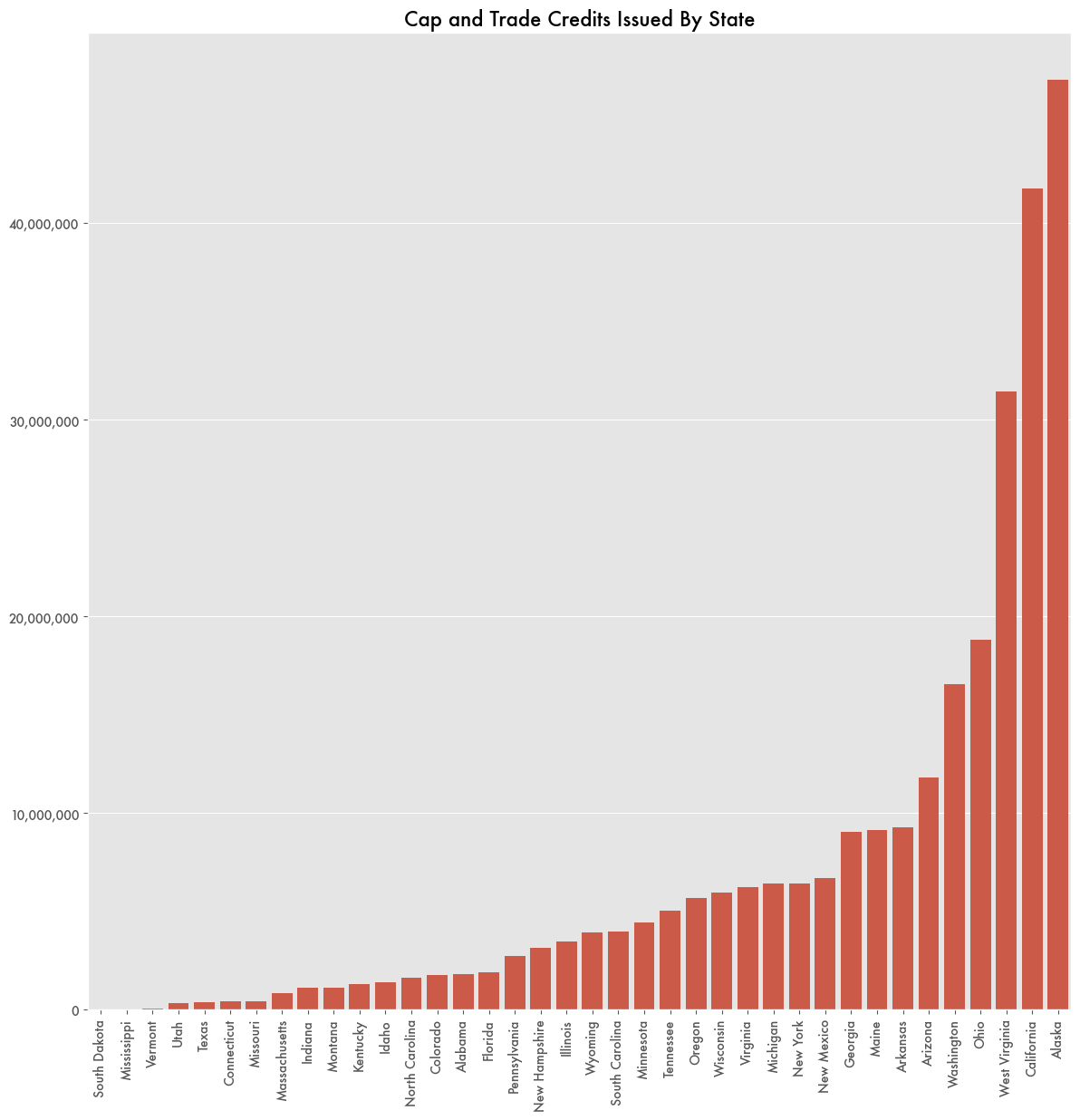

Of the 274 million credits issued since 2004, 17 percent were issued in Alaska alone, mainly to native tribes or native-owned companies, which means cap and trade likely brought the state somewhere between $700 million to $1.9 billion.

Refineries Paying the Bills

For the companies that purchase the offsets, it’s largely refineries. Based on data from 2018 to 2020, the top five purchasers are almost all refineries like Chevron, Philips 66, and PBF energy—Tesoro Refining bought 17 percent of those issued—but there are also concrete manufacturers and energy utilities like PG&E and the Southern California Gas Company.

One company that does not appear in the list is Exxon because the oil giant’s production operations have largely left the golden state. Exxon once had a major refinery in Torrance, California and various offshore production operations but those assets have since been sold off.

California’s refinery capacity has been in sharp decline in recent years with it’s focus on eliminating gas-powered automobiles by 2030 as well as recent laws forcing refineries to hold minimum gasoline inventories and to provide monthly reports, all to prevent price gouging.

California’s refinery situation has led to increased imports of gasoline from abroad. In past years, the state regularly imported refined gasoline from places like India and South Korea, but in 2024 total gasoline imports reached $2 billion—around five times what it was in 2018 ($419 million)—61 percent of that coming from India and South Korea—based on trade data from the U.S. Census.