DC Water’s Implausibly High Volumes

DC Water is the water and sewer authority for Washington D.C. and some parts of the surrounding Maryland and Virginia area. Their site describes treating 294 million gallons per day (mgd) on average through their advanced treatment plant at Blue Plains.

But it’s unlikely that they are handling that much, or if they are, they are not getting paid for it.

For example, the annual report for 2024 shows an operating revenue of $978 million based on water and sewer services for D.C. and just wastewater services for nearby Maryland and Virginia.

Based on recent charging rates posted on their site for just handling wastewater of $16.14 per 1,000 gallons for residential, that would put the daily wastewater usage at 166 million gallons as an upper estimate—about half of what DC Water is estimating. And that’s without factoring in all other sources of revenue besides wastewater usage (e.g. treated water, fees).

($977,982,000/($16.14 per 1,000 gallons))/365 = 166 mgd

DC Water’s water delivery numbers don’t really add up either. From 2015 to 2020, the utility reported delivering millions of gallons less per day on average when D.C.’s population was consistently growing by tens of thousands.

When the pandemic hit and D.C. saw a sharp population drop, water usage somehow grew as if fewer people started suddenly using more water.

Sewage Spill, Sewage Overflows, and Clean Rivers Project

Currently DC Water is the focus of what might be the largest sewage spill in U.S. history as a major pipe called the Potomac Interceptor broke in January spilling millions of gallons of sewage into the Potomac river.

While the details of the break are still being investigated, DC Water is being scrutinized for how it was spending money.

DC Water was in the midst of repairing the pipe close to where the break occurred as part of various system improvements, including the large scale Clean Rivers project. The latter is a $3 billion initiative to create multi-mile tunnels that can absorb combined sewage overflow (CSO)—sewage that gets sent into the Potomac or Anacostia rivers during periods of high rain because there is too much volume at one time for the system to handle.

CSO was already responsible for millions of gallons of sewage flowing into those rivers on an annual basis. The first part of the Clean Rivers project to tunnel underneath the Anacostia was completed in 2016 and the next portion dealing with the Potomac began in 2019.

Bond Pre-Funding and User Fees

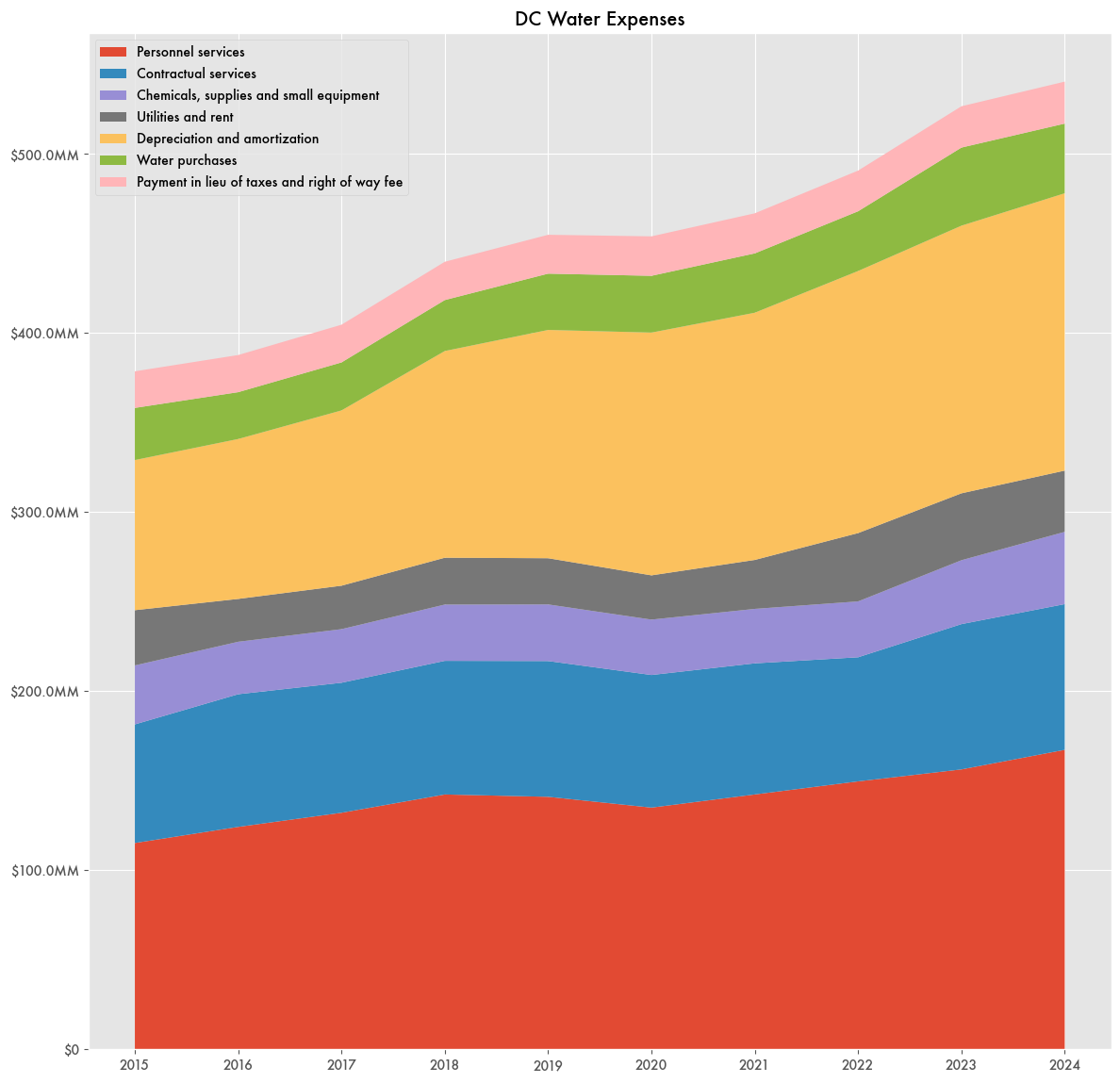

DC Water is funding the project largely through bonds, but then paying back the bonds through the Clean Rivers Impervious Area Charge (CRIAC) on customer bills, which now is on the order of $24 per equivalent residential unit. While the Potomac portion has just started, DC Water already made over $3 billion in bond offerings—likely a pre-funding of the project in advance—and is paying $146 million a year in interest payments—26 percent of its expenses for the year.

Altogether, with the CRIAC fee, DC Water bills now average around $147 per month for consumption of 4,024 gallons. While that is likely extremely high for the U.S., DC Water shows it as being average considering the high average income for the D.C. area. Yet customers are substantially further behind on payments—customer receivables, net of allowance for doubtful accounts—which was $49 million ten years ago now stands at $114 million.

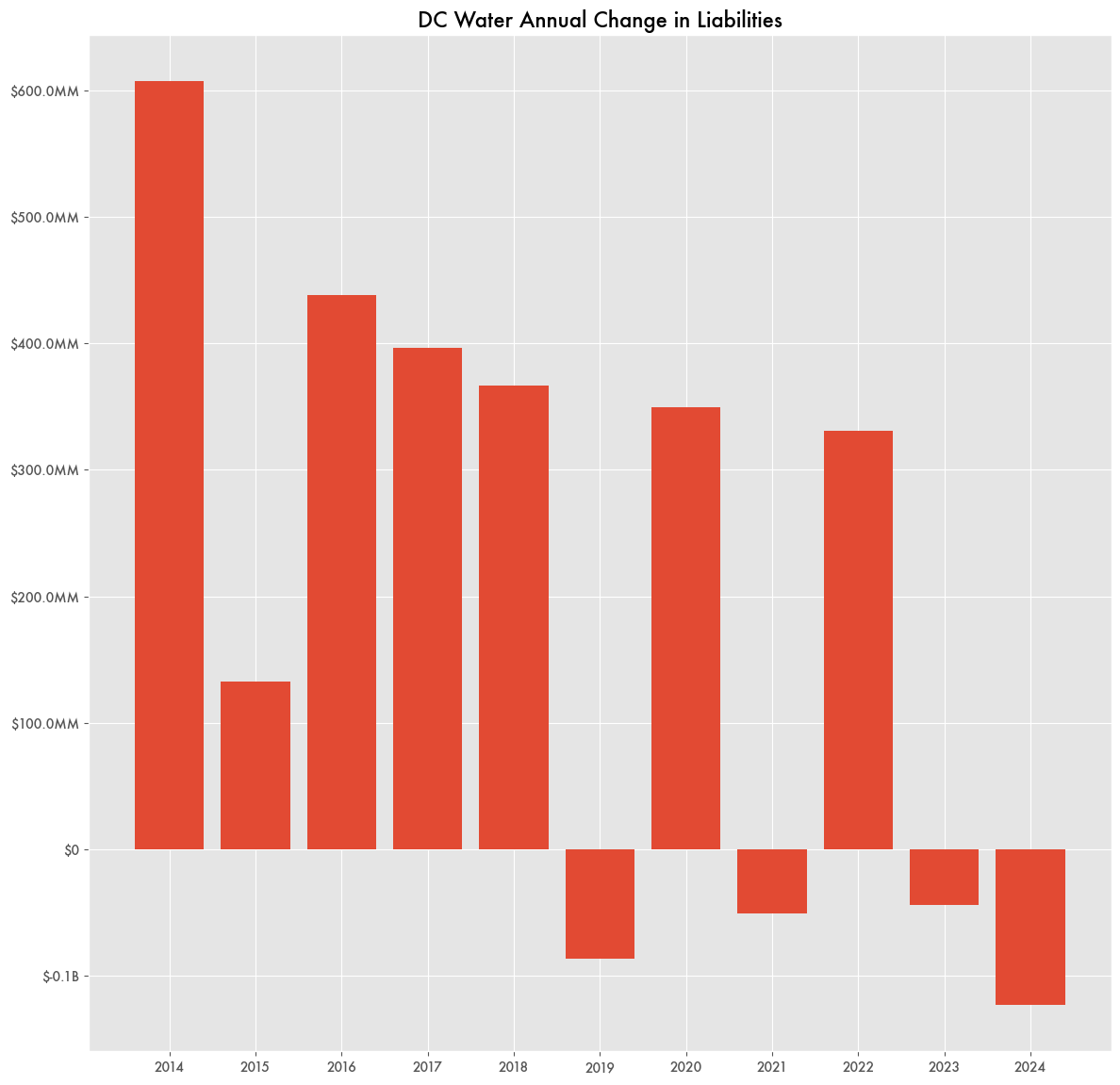

Even with the high user fees, DC Water has made little headway in paying off the debt. The most they paid down was in 2024 when liabilities decreased by $123 million—slightly less than their annual interest payments for the year. Since 2014, they have taken on about $200 million in debt a year.

Similarities to Jackson, MS

The story of a public water utility potentially falsifying numbers in the midst of sewage leaks and system repairs in very similar to that of Jackson, Mississippi.

In that city, records for water usage suddenly plummeted to a fraction of what they previously were following changes to the billing system. Similar to D.C., water usage didn’t follow distinct population trends.

In Jackson, the city was hemorrhaging residents, potentially related to sharp increases in water bills needed to help fund the ailing system, but the statistics kept showing high water use as if nobody had left.

With fewer residents to pay the bills, the system wasn’t bringing in enough revenue to pay for necessary repairs, leading to the complete collapse of its treatment plant and a citywide boil advisory for days in 2022.