Dollar Index Continues Its Ascent Despite Surging Inflation

Despite the steady growth in inflation over the last two years, the dollar index—a weighted average of the international value of the U.S. dollar compared to a basket of other currencies—continues to rise in line with inflation.

In general, the dollar index should decline with large inflation. If the dollar is worth less in the U.S., it tends to be worth less when traded for other currencies. For example, when Venezuela started seeing hyperinflation beginning in 2012, its value against the dollar plummeted.

In general, the two values should be inversely correlated: If inflation goes up, the dollar index would ostensibly go down.

But the opposite appears to be happening largely partially because other currencies have been affected by their own inflation as well, but also potentially due to a host of other factors affecting the dollar, like oil prices—which now appear to be directly correlated with the international value of the dollar.

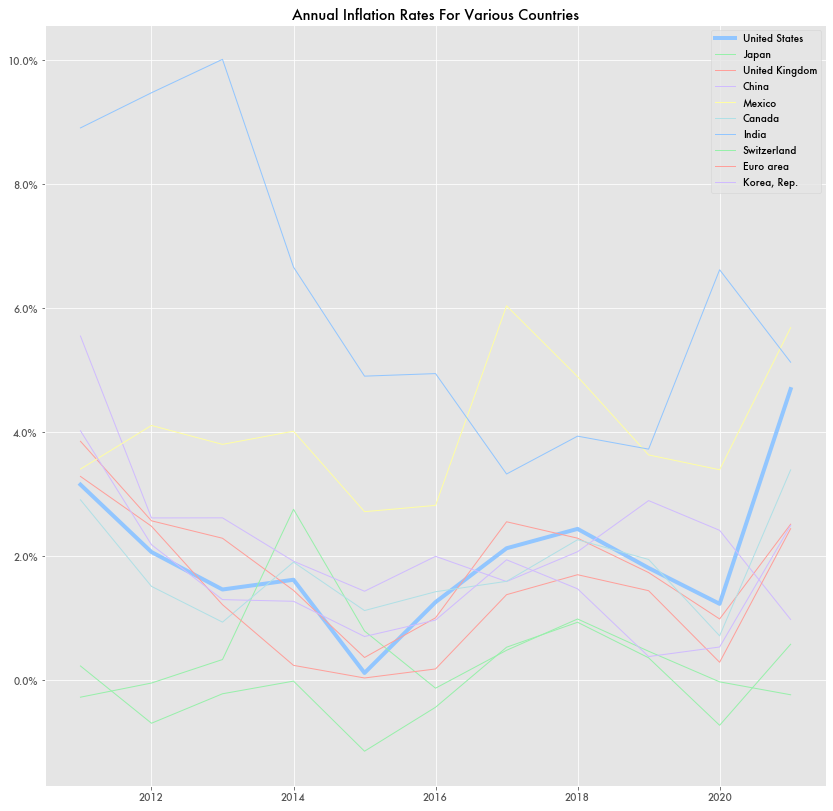

International Inflation

The Japanese Yen, the British Pound, the Korean Won, the Indian Rupee, and the Euro—top major currencies that affect the dollar index—have all been devalued compared to the dollar. That is, it takes more yen, not less, to buy a dollar now than two years ago. At the beginning of 2020, it was ¥108 to a dollar. Now it’s over ¥143.

The Chinese Yuan, Mexican Peso, Canadian Dollar, and the Swiss Franc also devalued over that period, but that was after a brief period of increasing value and are effectively back to where they were pre-pandemic.

The currencies that determine the dollar index are selected and weighted based on bilateral trade amounts. For example, changes in the value of the Euro, the largest trade partner, are weighted higher than that of the Venezuela—of which there is little bilateral trade with the U.S.

But the higher inflation rates in some of these countries doesn’t completely explain their currency exchange rates. While the Japanese inflation rate is at a relative high of 2 to 3 percent a month, it’s significantly less than recent U.S. inflation rates around 8 percent per month.

If you had ¥108 in 2019, the equivalent of one dollar at the time, it would be the equivalent of ¥110 in 2022 because of inflation. That’s nothing close to the ¥143 to a dollar currency ratio it stands at now.

Similar for the U.K. and South Korea: All are countries seeing higher inflation, but nothing close to the changes in exchange rates.

Other Sources Affecting Currency Values

While inflation is a major factor in currency valuation, other factors, like national interest rates, debt, and trade deficits play a role.

Anything that could make investors more likely to put their capital in that country and therefore trade into that country’s currency can affect values.

Since the dollar is considered a reserve currency—the default currency for major international exchanges, particularly oil, and held in large quantities by central banks—it’s also a safe haven for investors during tumultuous times, like a global pandemic, international inflation, and war in Eastern Europe.

That safe haven status may be leading to more U.S. investment. For example, foreign direct investment (FDI) into the U.S. has seen an upswing since the pandemic—up 747 percent since the beginning of 2020.

Strong Dollar and Trade

A high dollar index is considered a “strong dollar.” That is, it buys a lot in other countries.

The problem is that a strong dollar is the bane of domestic manufacturing. It means that domestic goods are more expensive to foreign consumers and has been a major contributor to the growing trade deficit that has plagued the U.S. for the last two decades.

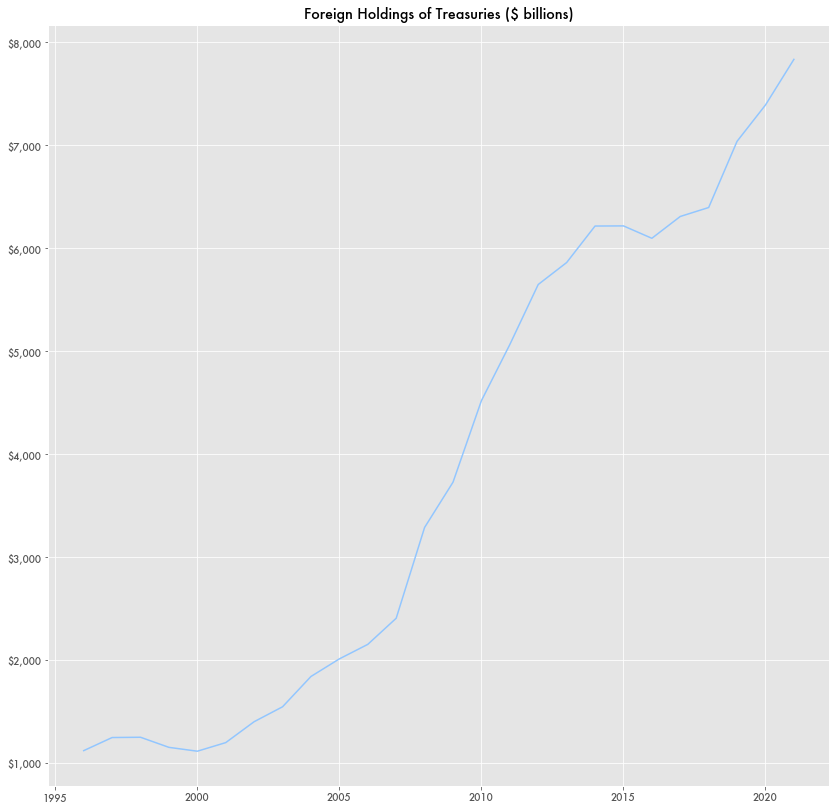

Pro-labor and pro-manufacturing advocates have been pushing for a weaker dollar for some time now, with much of that emphasis placed on what they call China’s currency manipulation. By buying U.S. treasuries in bulk, as well as inflating and/or devaluing their own currency, China helps prop up the dollar’s value, making imports from China to the U.S. cheaper.

Foreign holdings of Treasury securities, something that had been flat between 2014 and 2016, has seen almost an additional $2 trillion held in the last four years based on Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (Sifma) data.

The recent rise in interest rates also means higher returns on treasuries. That in turn makes treasuries more compelling to investors, both foreign and domestic.

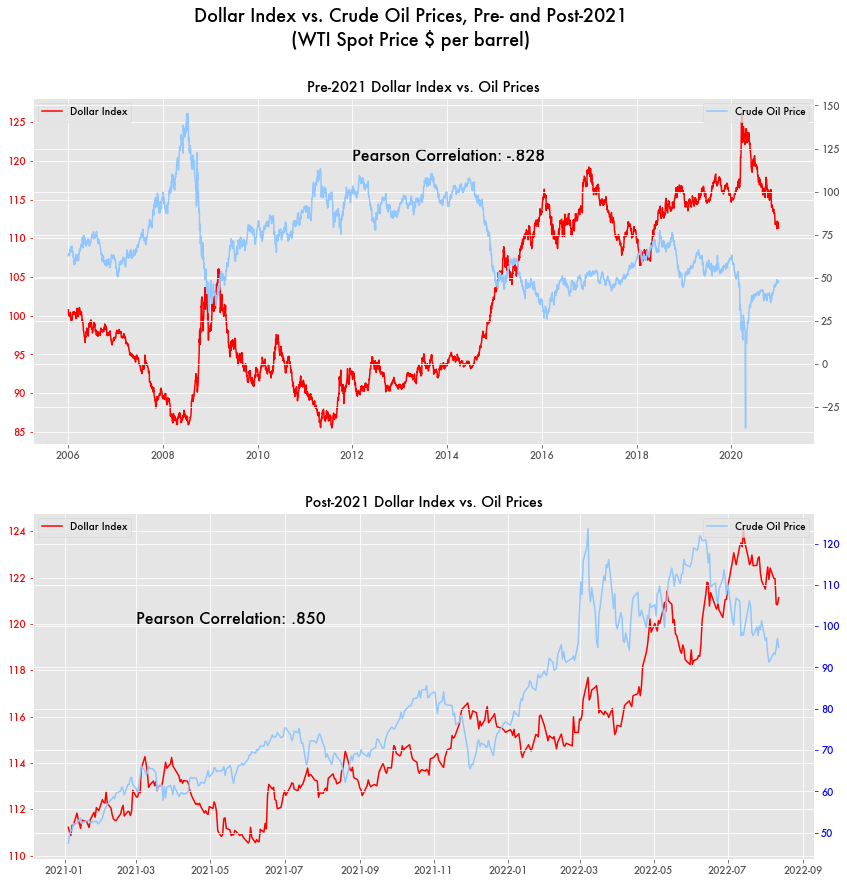

Oil-Dollar Correlation Inverted in 2021

One potential driver of the dollar index is oil prices. Since 2021, oil prices and the dollar index have moved almost in tandem.

With the price of crude oil now almost twice what it was pre-pandemic, much more money is needed to buy the same amount of oil. And since the U.S. dollar is the global reserve currency, more U.S. dollars are needed to buy and sell that oil.

For those countries that are seeing modest inflation, oil investors might want to exchange their yen, loonie, or peso now before fluctuating exchange rates make the oil that much more expensive.

Yet the correlation between the dollar index and oil prices isn’t a given. Before 2021, oil prices and the dollar index were actually inversely correlated.

When one went up the other would tend to go down and vice versa (Pearson correlation: -.828). When oil prices collapsed for a brief period during the pandemic, the dollar index shot up.

But something switched in 2021. With the Russia-Ukraine war in full effect, both increased in tandem (Pearson correlation: .850) through August of 2022.

Only in the last few months have the two separated again, with oil prices declining and the dollar continuing to increase as interest rates have increased.

While a strong dollar is generally bad for U.S. exports, the dearth of Russian oil means that U.S. oil is still in high demand despite the relatively higher cost.