Great Barrier Reef Coral Suddenly Return, But Was It Ever Actually Dying

For decades, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef was said to be in decline from bleaching events—sudden changes in temperature that shift the balance of its ecosystem causing corals to turn white.

The change is commonly ascribed to climate change. Coral reefs are hypersensitive to even small changes in temperature, so even a one degree Celsius increase in sea temperature over the last decade can cause the algae that lives within coral, zooxanthellae, to be expelled, exposing the coral’s white skeleton.

But the corals at the Great Barrier Reef have rebounded, and in 2021 they saw such massive growth to the point where it has the highest coverage in recorded history based on available data from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS).

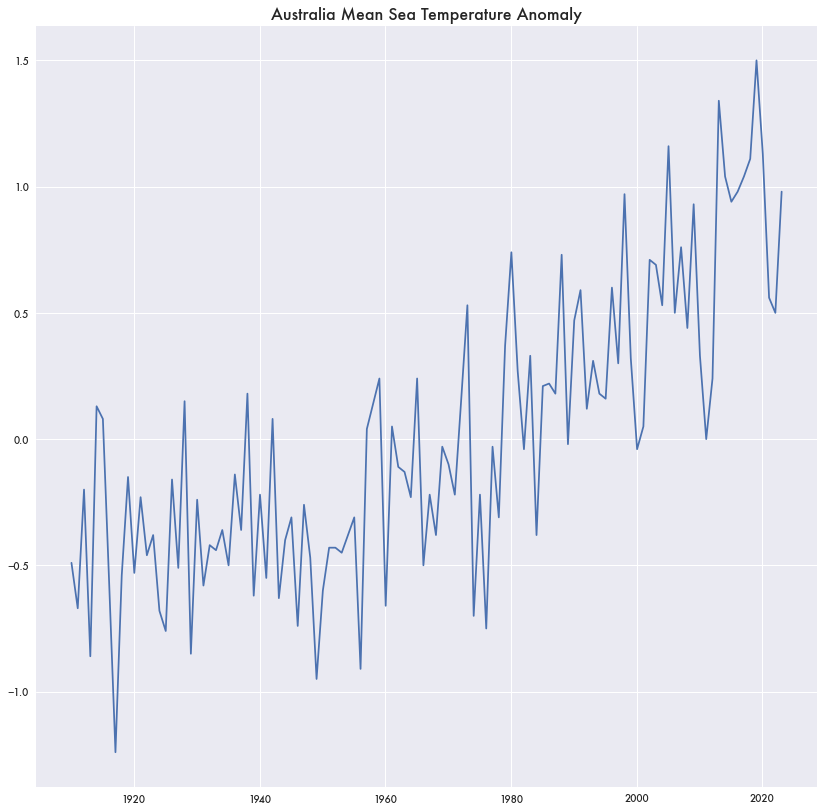

That rebound occurred despite steadily growing sea temperatures and major bleaching events in 2016, 2017, 2020. and 2022. NOAA declared the 2014-2017 bleaching event the “longest, most widespread, and most damaging coral bleaching event on record,” covering 93 percent of the reef. Mean sea temperatures in Australia continue to climb as 2019 had the highest temperature anomaly on record—1.5 degrees Celsius.

Corals have also recovered despite the steady growth of the crown-of-thorns starfish population—a large marine invertebrate that feed on the coral. Major storms—another source of coral destruction—didn’t seem to make a dent either as tropical cyclones Tiffany, Trevor, and Penny all swept through Australia in the last five years.

While bleaching is considered a threat to the biodiversity of coral reefs, it doesn’t mean the corals are dying. They are more at risk to death and disease when this happens, but the coral is still alive.

And while coral coverage waxes and wains for various reasons year to year, there is little sign of dead coral following most bleaching events. Outside of 2017, the data shows little change in the amount of dead coral, so the appearance of white coral may simply be a remnant of common ecological cycles of the reef.

Photo Transect Survey Shows The Bleaching Cycle

That data comes from the AIMS manta tow survey, where a boat pulls a surveyor with scuba gear underwater who then counts the coral and wildlife in each surveyed area.

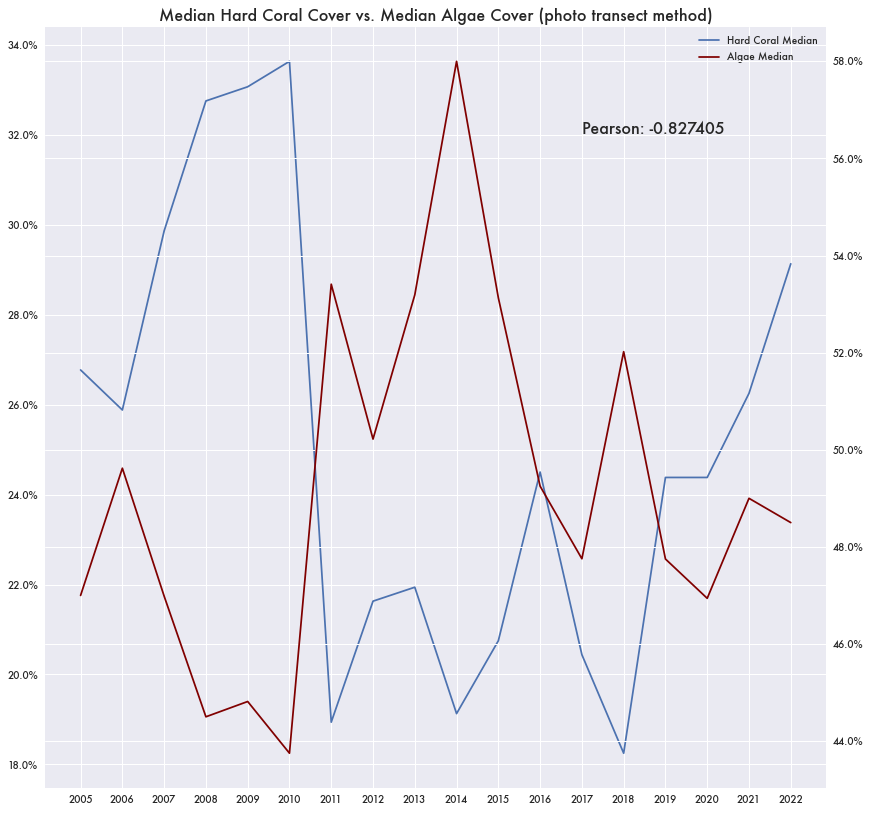

The AIMS photo transect survey—data retrieved from pictures taken underwater of 50 meter segments of reef—also shows historically high levels of hard coral as well as the sharp decline in the early 2000s when the crown-of-thorns starfish population exploded.

That survey data also includes algae coverage levels, which show how coral levels inversely relate to algae levels (Pearson: -0.8274).

Otherwise known as the bleaching cycle, as the hard coral population collapsed in 2011, corals expel the algae into the water and algae coverage grew. As corals have rebounded, they are consuming more algae and algae cover is declining.

The bleaching cycle is driven by El Niño weather patterns every three to four years. Periodic warmer temperatures lead to more algae and more bleaching. Periodic cooler temperatures lead to less algae and more coral.

The combination of the El Niño weather pattern combined with the La Niña weather pattern on Australia are what’s called the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). It’s a pattern that rotates between months of warmer than usual weather (0.8 °Celsius above average) with less rainfall (El Niño) versus cooler temperatures (La Niña).

While overall higher temperatures from climate change might lead to more bleaching during El Niño, the coral aren’t necessarily dying and they are returning en masse during La Niña periods.