How The Health Insurance Index Skews Inflation and Hides Rising Costs

When economic numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) were announced November 14th, it showed a lower than anticipated inflation rate. Much of that was due to the declining price of gas, but what was also unique was that the health insurance price index—an adjusted metric for how the BLS measures the cost of health insurance—went down by 34 percent.

A decline of 34 percent of any price index is significant, and it feeds into the overall consumer price index (CPI)—the BLS metric that determines inflation based on the overall cost of goods and services—which affects the economy as a whole.

The BLS site notes that they have recently implemented smoothing into the equation that determines the health insurance index because the measurement can be so volatile.

But while smoothing could have affected the health insurance index slightly in recent days, that metric has been flawed going back decades.

Instead of measuring health insurance by the cost paid by consumers, the health insurance index is measured indirectly by the net profits earned by health insurance companies.

Otherwise known as “retained earnings,” it’s intended to measure the net amount spent on medical care rather than the insurance itself.

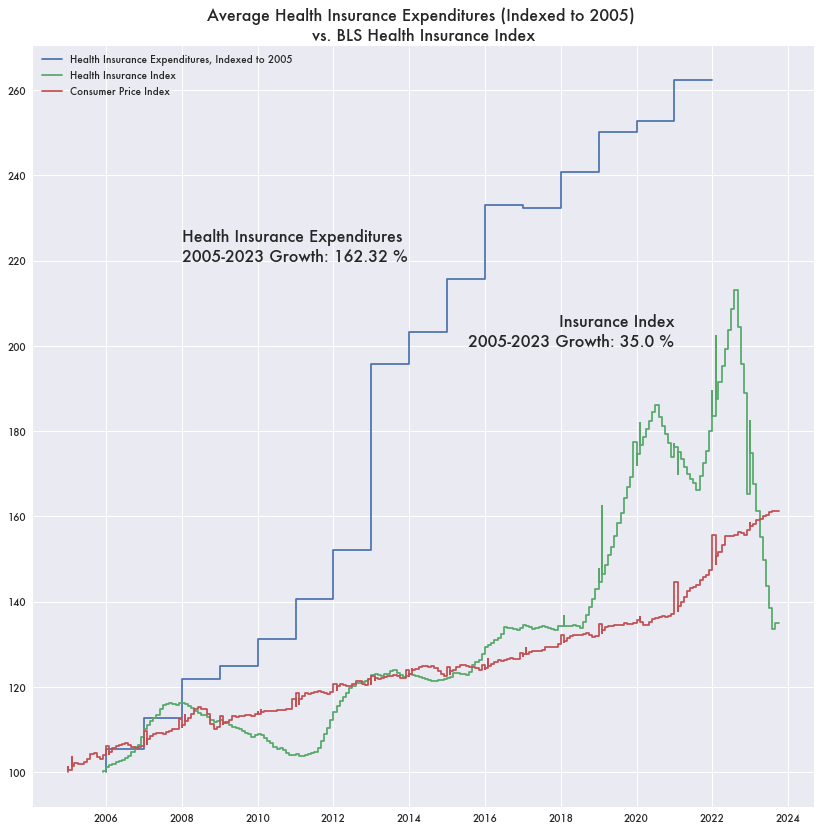

But measuring health insurance spending this way obscures the quickly rising price of health insurance. The health insurance index has only grown 35 percent since 2005—in line with inflation—but average health expenditures have grown over 162 percent in the same period based on BLS data.

As a percentage of total household expenditures, health insurance went from 2.6 percent to over 5.2 percent.

Other types of consumer insurance costs—like car, home, and life insurance—are not measured indirectly this way. They also haven’t seen the same kind of escalating annual expenditures as health insurance.

Divergent and Volatile

And it’s not just sharp division in the total amount being spent, the health insurance index is substantially more volatile. Health insurance expenditures have been growing steadily, yet the health insurance index grew until it suddenly collapsed last year, leading to the 34 percent decline previously noted and the BLS’s need to smooth out the data.

Few other price indexes ever see sharp swings like this. It would be as if the average price of eggs went from $4 a dozen to $8 then back down to $4 within a few years.

Ostensibly, the index increased because insurers were earning larger profits for years until after the pandemic.

Implied Rising Medical Costs

According to the BLS page on medical price indexes, the retained earnings are based on the following formula.

If total premiums are going up as shown by rising health insurance expenditures, but retained earnings haven’t increased much beyond inflation, that implies the amount of total medical benefits has also increased substantially.

That either implies that the cost of medical care paid out by insurance is rising significantly above inflation or a much larger quantity of medical services are being provided. That would be a lot of additional medical care across the country to account for a more than doubling of expenditures in 15 years.

If it’s a higher medical costs driving total benefits, then those rising costs don’t show up in inflation because they are buried in the health insurance index.

The indirect approach that uses retained earnings has been in debate for some time, but according to the BLS there are practical reasons for its use.

According to their documentation, previous direct methods tried to account for price changes in medical care and adjust the index accordingly—like accounting for the price of a night’s stay in a hospital bed—but the indirect method improves upon that by somehow accounting for the underlying quality of the healthcare provided:

Although perhaps second best conceptually, the indirect method represents a pragmatic approach that at least partially reflects quality change and care utilization. The indirect method has practical advantages and therefore should, in the short to medium run, continue to be the method for pricing health insurance in the CPI.