In economics, the Philips curve is the theory that wages tend to be inversely related with unemployment. More often it is extrapolated to infer that inflation is inversely related with unemployment. When plotted on a chart, the relation between the two metrics forms a curve.

That is, as more money enters the economy and prices rise, unemployment goes down and vice versa. More money circulating leads to more jobs.

In 1968, economist Milton Friedman vocally criticized this theory, predicting that inflation could occur alongside rising unemployment, contradicting the current Keynesian theories of economics.

His prediction of what would later be termed “stagflation” came true in the mid-seventies. Rising inflation led to rising unemployment, not the other way around. Friedman would go on to win the Nobel Prize and other accolades partially based on his predictive prowess.

But Friedman’s prediction wasn’t that random. Rising inflation alongside rising unemployment was already occurring in 1968—the same period Friedman made his prognostication.

And in general, there are many other factors that can lead to rising or falling unemployment besides inflation, like debt incurred from spending on the Vietnam War and, more specifically, interest rates—something not largely mentioned by Friedman.

Otherwise known as the Federal Funds rate, it’s the rate at which banks pay interest on money they borrow from the Federal Reserve. The Federal Funds rate affects most other interest rates, and therefore the cost of borrowing money across the economy. Higher costs of borrowing money affects whether a business can borrow funds to invest in production and employ more workers, also known as a recession.

When the Fed started raising rates in 1968 during Friedman’s pronouncement, it also led to a spike in unemployment a year later—termed the Guns and Butter Recession.

Prior to that, the Investment Bust Recession of the late fifties saw a significant increase in unemployment following a marked increase in interest rates over the previous three years.

During the severe recessions of the late seventies and early eighties—also known as the Volcker Recession—Fed chairman Paul Volcker raised interest rates to historic levels—over 18 percent—to wring out inflation, intentionally forcing a recession that would lead to an almost 11 percent unemployment rate—the highest in the last 80 years outside of the pandemic.

Upset with how Fed policies were crippling the economy, the construction industry mailed bricks and two-by-fours to the Fed as a show of protest.

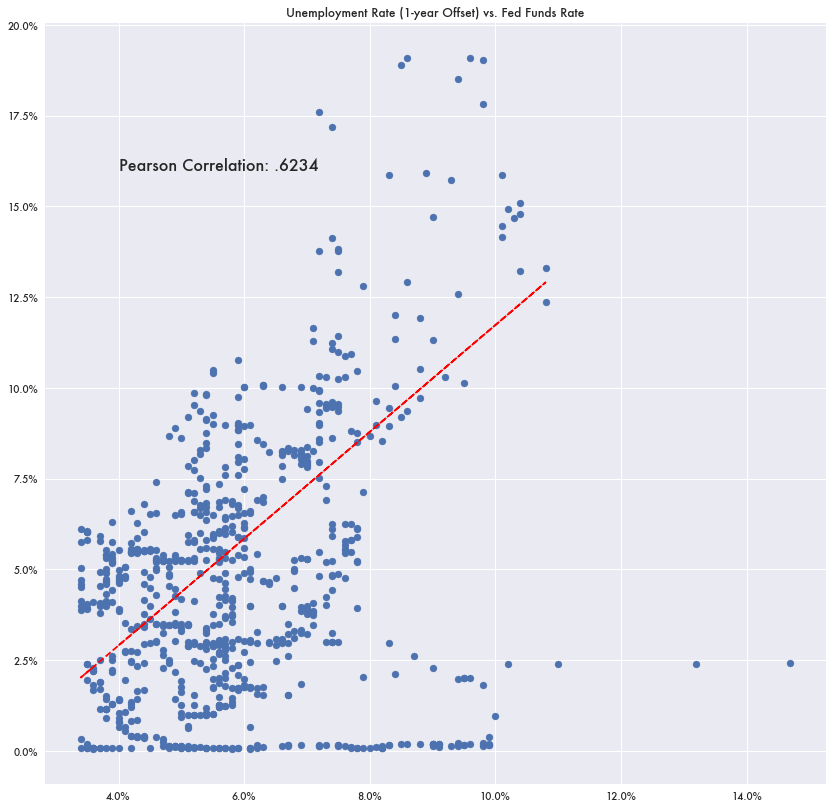

The Fed Funds-Unemployment Correlation

While the Philips curve shows a correlation between inflation and unemployment in the short-term, the inflation rate has no discernible correlation with unemployment whatsoever in the long term (Pearson Correlation: .0091)

But the Fed Funds rate substantially correlates with the unemployment rate using a one-year offset (Pearson Correlation: .6234).