During the Nye committee of 1930s, Congress investigated the influence of financial interests on the decision for the United States to enter World War I.

Headed by Senator Gerald Nye from North Dakota, it delved into whether there was basis for widespread reports that munitions manufacturers, who made huge profits during the war, pushed the country to war for their own benefit and might do so again. Representatives from major interests testified about their financial ties, including the bank J.P. Morgan and chemical giant DuPont, which produced gunpowder.

Eventually the committee would publish multiple reports on the influence of the munitions industry, wartime taxation, price controls, and naval shipbuilding, but the committee stopped short and never produced any substantial findings on J.P. Morgan.

J.P. Morgan was suspected of heavily influencing the U.S. effort to join the war as the bank’s financial investments in war industries, both in the U.S. and Europe, earned them an incredible windfall.

Financial Ties to the War

The current J.P. Morgan website proudly boasts of the company’s support for the Allies at the time:

During World War I, J.P. Morgan & Co. arranges the largest foreign loan in Wall Street history – a $500 million bond issue to support the English and French governments – and acts as purchasing agent for the Allies, facilitating the purchase of over $3 billion worth of war material and other goods needed by the Allies.

Right at the outset of war, Morgan was designated the exclusive purchasing agent for Britain in the U.S., one of the most lucrative single contracts in American history, earning the company $30 million.

The U.S. government was also pressured to guarantee Morgan’s loans to the allies to keep the flow of munitions going to Europe, without which the Allies would likely lose. That would eventually draw the U.S. further into the conflict.

According to the book, Warhogs: A History of War Profits in America:

The Morgan loans became a source of controversy in one other way. By 1917, when the United States declared war, Britain and France had run out their line of credit. Private investors could no longer safely loan money to these insolvent governments, so the Wilson administration faced an unwelcome decision. The United States had either to guarantee the repayment of the Allied loans, or shipments of war materiel must cease. Since the latter was totally unacceptable—it would mean defeat—there really was no choice in the matter Wilson’s inevitable pledge of repayment thus guaranteed that Morgan and other bankers would be reimbursed in case the Allies defaulted.

J.P. Morgan would also benefit after the war was over through heavy investment in German reconstruction loans.

Advocating For War

Morgan and others went beyond simply benefitting from the conflict but actively advocating for U.S. involvement.

Both Morgan, DuPont, and other defense contractors were supporters of the National Defense League, a campaign finance committee that funded the opponents of isolationist, anti-war politicians.

Far before the Nye committee, Congressmen Oscar Callaway from Texas would accuse Morgan of explicitly running a media campaign to drum up support for entering the war. According to a Congressional Record of 1917:

In March, 1915, the J. P. Morgan interests, the steel, shipbuilding, and powder interests, and their subsidiary organizations, got together 12 men high up in the newspaper world and employed them to select the most influential newspapers in the United States and sufficient number of them to control generally the policy of the daily press of the United States.

It goes on to detail how they purchased the control of 25 papers and furnished them with editors that focused on militarism and the war effort and the threat of being attacked by foreign adversaries.

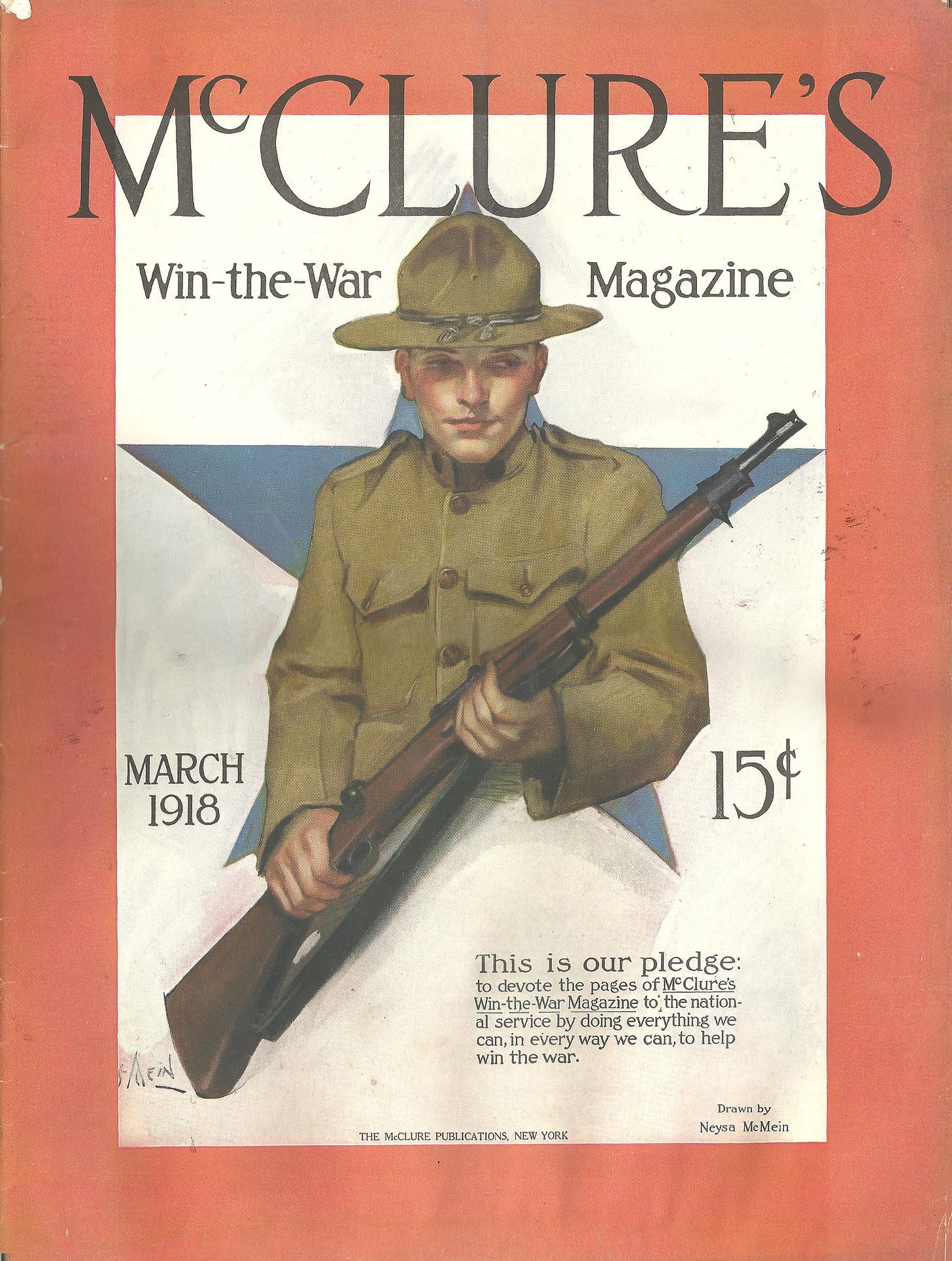

The record doesn’t mention the names of the newspapers bought, but, according to the book House of Morgan, around that same time is when J.P. Morgan bought up the McClure’s newspaper syndicate sub rosa through an associate named Brainerd. McClure’s had been publishing muckraking journalism for some time, covering the major trusts of the era with writing from the likes of Upton Sinclair and Ida Tarbell.

But eventually McClure’s was mired in debt, and Brainerd bought it up just as it began an investigation into J.P. Morgan’s money trust. Morgan also looked into buying up other newspapers in major cities across the country, including the Washington Post, but eventually backed down.

Under new ownership, McClure’s content went from stories about the pride of the fighting men of Germany in 1912 to multiple cover stories about the need to win the war against Germany in 1917 and 1918.

As part of that same Congressional record, Congressman J. Hampton Moore called attention to false reports of ships being sunk by German U-boats, like that of the H.M.S. Housatonic, the H.M.S. California, the steamship Turino, and the steamship Philadelphia. To Moore, these were all attempts to falsely drag the U.S. to war.

While these reports jostled the public into a frenzy, there was little risk to the U.S. fleet. The Philadelphia safely arrived in port. An American named George Washington was reported to have died on the British Turino when it was hit by a German U-boat, but he was actually British.

But while previous reports of risk to the U.S. fleet may have been overhyped, eventually, German submarines would torpedo the R.M.S. Lusitania on its way from New York City to Liverpool, killing over a thousand on board. Along with the Zimmerman Telegram, it would inspire the U.S. to join the war effort as an ally.

Who's the author of the book 'House of Morgan' that you mention? I think there's more than one book with that title.

Which newspapers, which magazines?

Well, one group saw an opportunity, needed the U.S. 'in,' and got them in.

See also another of their projects, the 'Balfour Agreement'