Latvia, Russia Figure Prominently in FinCen Leaks

In September of this year, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) released the FinCen Files—a leak of suspicious activity reports (SARs) from the U.S. Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCen).

SARs are notices of potential money laundering or other illegal activities that banks and other financial institutions are required to file. While the leak only compromises approximately two percent of the SARs that are filed—about 2,100 transactions between 1999 and 2017 representing over $2 trillion that came out of the Mueller investigation—and SARs are not necessarily associated with illegal activity, the leak provides a glimpse into a narrow band of the world of international finance.

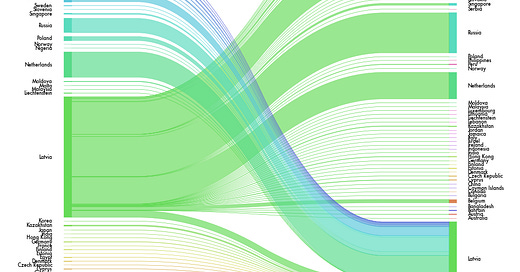

Of those SARs in the leak, the vast majority are associated with two countries: Latvia and Russia. Together they represent over 33 percent of the banks where monetary transactions originated and 21 percent of the banks that benefitted from the transaction. From those two countries, money largely moved to either Latvia, Russia, Netherlands, or Switzerland.

While certain large international banks like Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered, and Credit Suisse appear frequently in the leaks, most of the transactions involving Latvia and Russia were dominated by two banks, Rigensis and Rosbank for Latvia and Russia respectively. Most other transactions involved smaller, local institutions. Latvia financial enforcement body fined Rigensis in 2019 for lax anti-money laundering restrictions.

Latvia may stand out because it became a hub for bank secrecy and money laundering over the last three decades. A number of the banks listed in the FinCen Files related to Latvia, such as Trasta Komercbanka and ABLV Bank, have since collapsed in scandal, and others like Industra, RIB, and Expobank are known for catering to international offshore accounts. The former prime minister of Latvia, Valdis Dombrovskis, told ICIJ that the country made numerous efforts in the last decade to reform the banking and close the secrecy loopholes.

Russia and the Laundromats

Russia's prominence in the leaks is also not surprising as numerous international money laundering scandals in the last decade involved money exiting Russia's coffers. In particular, the Troika Laundromat—a collection of offshore entities used to launder money from Russia to the West surrounding Troika Dialog, a large private investment bank in Russia—may be relevant to the FinCEN files.

Prevezon Holdings, a small international real estate firm, was accused of receiving funds associated with the Magnitsky fraud—a large scale tax scheme in Russia through the Troika Laundromat and information related to that transaction showed up in FinCen Files according to an analysis by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

Prevezon also appears in the Mueller Investigation of Donald Trump as the company paid a lawyer, Natalia Veselnitskaya, to pass along information on Hillary Clinton to Donald Trump's son in exchange for leniency in money laundering enforcement charges.

Bill Browder, the American that headed the Russian investment firm Hermitage Capital, was accused by the government of masterminding the Magnitsky fraud, although Browder denies the charges and has since become an anti-corruption advocate targeting the laundromats.

Besides the Troika Laundromat, there is the Russian Laundromat—also a collection of offshore financial institutions accused of being a conduit for money laundering out of Russia—that involved banks in Latvia, Russia, Moldova and a host of other countries.

The Russian Laundromat operated around 2011-2014 and the Troika Laundromat operated around 2006-2013. The FinCen File data effectively starts in 1999, but most transactions are between 2011 and 2018.

BNY Mellon Bank’s History with Russia

The vast majority of the reporting of SARs in the FinCen Files was done by The Bank of New York Mellon (76 percent).

It was back in 2009 that BNY Mellon found itself on the other end of Russian money laundering. The bank settled a massive money laundering case with Russia over transactions that occurred in the 1990s where a couple illegally wired over $7.5 billion from Russia to BNY accounts. Russia had sued the bank under U.S. RICO laws for $25 billion but eventually settled for $14 million.

Coincidentally enough, the 1990s transaction with BNY Mellon was associated with someone who also appears in the FinCen Files: Semion Mogilevich—a Ukrainian living in Russia accused of being a criminal mastermind. One of the SARs associated with J.P. Morgan notes that an offshore enterprise initiating a transaction, ABSI, was affiliated with Mogilevich.

Mogilevich is regarded by the U.S. as a prominent member of Russian organized crime and wanted by the FBI for a multimillion dollar investment scheme. According to a BBC documentary, the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs believes he is one of the “top crime bosses in Russia and an authority on Russian organized crime,” and he’s been accused of everything from arms dealing to trading nuclear material, prostitution, drug dealing, oil deals, and money laundering. But Mogilevich has repeatedly denied accusations.

In testimony to the House Intelligence Committee, Glenn Simpson of the research firm Fusion GPS described Mogilevich as connected to a Russian gang, the Solntsevo brotherhood, which was attempting to blackmail Prevezon Holdings.