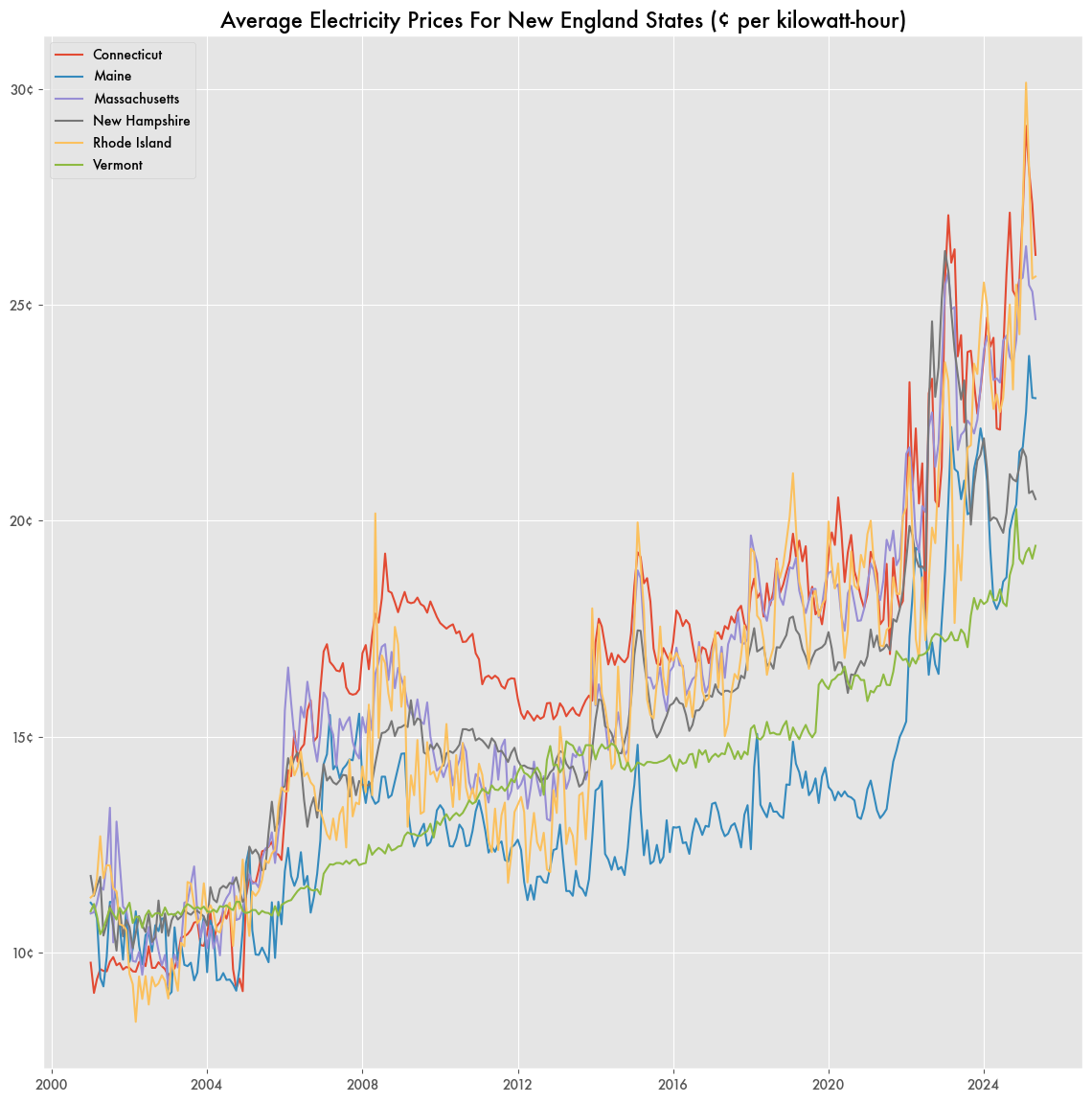

Maine's Renewable Push Turns it From New England's Cheapest Electricity to One of Its Most Expensive

In 2019, Maine updated its renewable portfolio standard (RPS) under Governor Janet Mills to make a more aggressive push for Net Zero and achieve 80 percent renewable energy by 2030.

The previous standard set in 2007 had already pushed the state to implement more wind power, which went from nothing in 2006 to 24 percent of generation in 2019 (2.5 terawatt-hours) based on Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. Now the state was doubling down.

Maine would ostensibly be suited for a heavy renewable portfolio as it already gets a large portion of its energy from hydroelectric power through numerous dams across the state and in Canada, plus it’s one of a handful of states with significant biomass generation—burning wood pellets for electricity and home heating that are sourced from nearby forest industry operations like paper mills that use every part of the tree.

But biomass has been in sharp decline for electricity generation since 2014. According to advocates for the logging industry, the northeast biomass industry was hampered by competition for electricity generation from cheap natural gas as well as competition from Canadian imports, whose Loonie made Canadian energy and biomass products significantly cheaper.

In 2016, the state legislature and then-Governor LePage would step in to help bailout the Maine biomass industry by providing $13.4 million in above-market payments at six plants. While that subsidized the industry, biomass continued to decline as a source of renewable energy generation. What was once 4 terawatt-hours of generation a year is now down to 1.5. Biomass plants stayed open but without providing as much electricity to Maine.

That became problematic as natural gas prices ceased to be cheap in 2020 following the Russia-Ukraine war. The push for renewables moved Maine away from natural gas reliance, but it has since come back after 2019.

Like a lot of New England, Maine leans heavily on natural gas yet has little access to it. While Maine had numerous gas pipelines built in the 1990s and early 2000s coming from other U.S. States and Canada—like the Tennessee, Maritimes & Northeast, Portland Natural Gas Transmission System, and Brunswick pipelines—few have been built since with projects like the Northeast Energy Direct getting shut down following local environmental complaints and concerns about costs. Attempts at getting LNG ports built had similar issues.

With rising natural gas prices, Maine quickly went from having the cheapest average prices for electricity in New England to one of the more expensive ones, and it had the largest price increase of any state over the last ten years. What was usually below 15 cents a kilowatt-hour is now closer to 24 cents.

Higher Spending on Renewable Credits

Maine would also spend $60 million more on renewable energy credits (RECs) in 2022 than it did the year before, with the large majority of that going toward hydroelectric power but also some biomass. Most of that was driven by the price of certain RECs increasing six-fold since the changes to the renewable energy portfolio and increased price of natural gas.

Higher Prices Benefit Canada

While natural gas prices are a large driver of electricity costs, it has driven the state to find cheaper electricity elsewhere. The pine tree state would spend heavily on imports of electricity from Canada, importing $378 million worth in 2023—about $187 million more than it spent fifteen years earlier—usually through New Brunswick.

The Central Maine Power Company—which serves the vast majority of lower Maine—would spend about $100 million more on purchased power in 2023 than it did in 2018 based on annual reports.

Yet even the large amount of local hydroelectric power produced in-state is secretly Canadian. One Canadian company, Brookfield Renewable, is the owner of dozens of dams throughout the state that produce 87 percent of the hydropower in Maine, which winds up being 21 percent of total state energy generation.

Brookfield, once owned by the Bronfman family, is in turn owned by a larger opaque investment firm that also invests in various other global energy resources like Brazilian gas pipelines and Indian telecom towers, and has been known for odd activities, like selling itself real estate.