No Recent Decline in Outgoing Longwave Radiation

The greenhouse theory posits that greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane act like a greenhouse for the atmosphere. They allow in solar radiation but prevent outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) from escaping. The more greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, the more radiation is prevented from escaping and is instead absorbed into the atmosphere, leading to an increase in temperature.

But data from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) High Resolution Infrared Radiation Sounder (HIRS) shows no recent decline in outgoing longwave radiation. Since 2000, measurements of average radiation for all locations have shown it to be largely flat—although it was in steady decline before that in the 1990s.

HIRS is a collection of satellites that track visible and shortwave radiation from Earth to measure a variety of climate metrics like temperature, wind, precipitation, ozone, cloud size, as well as non-visible radiation.

Ostensibly, if more radiation is being absorbed by greenhouse gases, less is making it out of the atmosphere and there should be a steady decline throughout. The sudden switch from decline to constant increase doesn’t make much sense as it would imply a large global shift in climate or solar radiation to account for such a change.

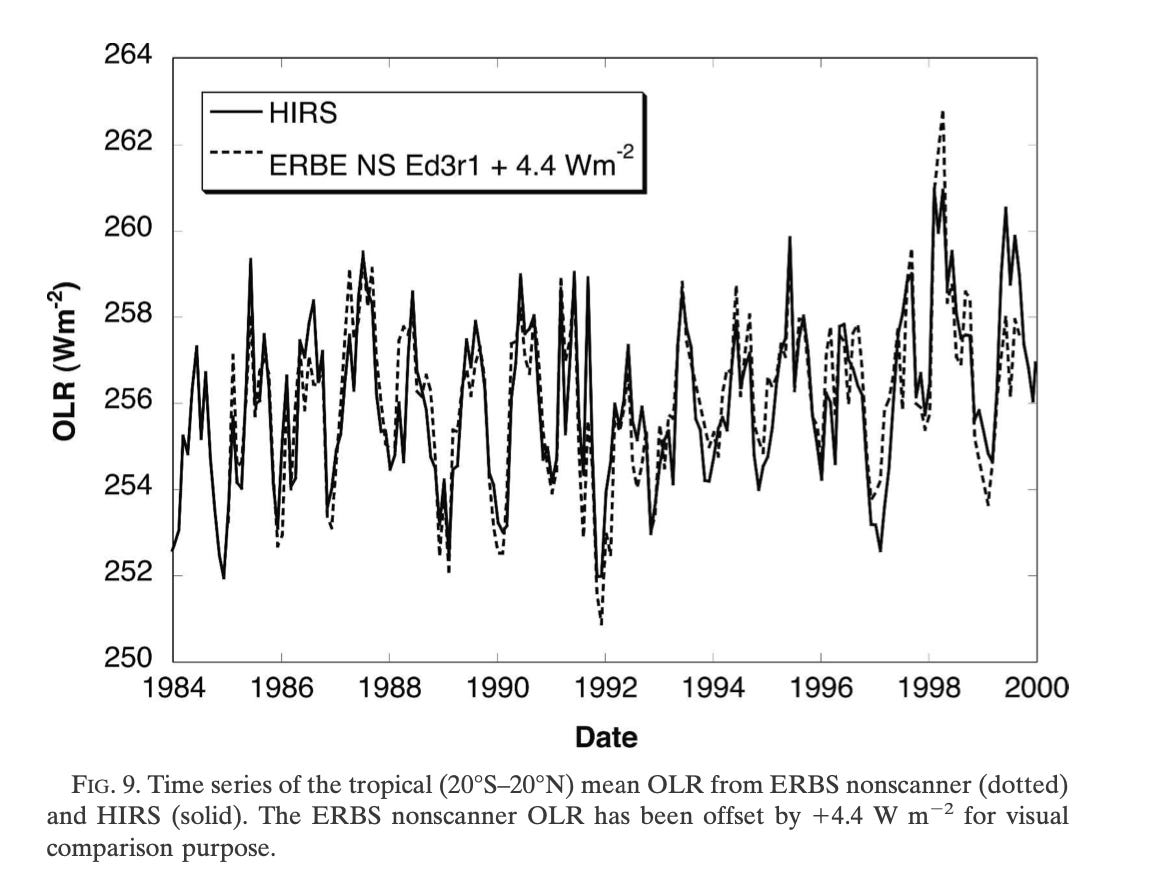

Additionally, research from the Cooperative Institute for Climate Studies/Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center at the University of Maryland on the HIRS data appears to show no distinct decline in outgoing longwave radiation either. The paper is largely focused on the accuracy of HIRS’ measurements, but the time series data it presents shows no indication of radiation being absorbed, unless more radiation was being added. From tropical locations (20°S–20°N), the average OLR appears to be increasing.

Greenhouse Theory Debate

While the greenhouse theory is currently accepted as scientific dogma, it was heavily debated throughout the 20th century and still elicits some confusion to this day.

For example, the University of Calgary has a site dedicated to informing the public about the greenhouse effect and how it works, preventing longwave radiation from escaping. According to the site, that is the only way that the Earth loses energy.

Since Earth is surrounded by the vacuum of outer space, it cannot lose energy through conduction or convection. Instead, the only way the Earth loses energy to space is by electromagnetic radiation.

But that is not true. The Earth loses energy through the displacement of the atmosphere similar to convection, otherwise known as atmospheric escape. Molecules of hydrogen and helium, the lightest gases in the atmosphere, escape at a rate of about 3 kilograms and 50 grams per second respectively according to a paper from the University of Washington. According to the European Space Agency, it is 90 tons of matter per day.

Convection usually involves two substances transferring heat, but in this situation space is a vacuum and has no matter to exchange. But still, the loss of mass from the atmosphere is a loss of heat.

Assuming a temperature in the stratosphere of 1,000 Kelvin and the specific heat for hydrogen of .769 Joules per gram, a loss of 3 kilograms of hydrogen loses 2.3 million Joules per second—smaller than that ascribed to longwave radiation but not an insignificant amount.

Molecules can escape the atmosphere through a number of different pathways: Jeans escape, hydrodynamic escape, photochemical escape, sputtering escape, charge exchange escape, and polar wind escape. They are all different ways that a molecule can collect enough energy to get away from the gravitational pull of the Earth.

Greenhouse Effect Debate

The University of Calgary is not the first to ignore the loss of heat through convection. According to a history of climate science from the American Institute of Physics, Svante Arrhenius the father of the climate theory and a Nobel Prize winning chemist in the late 19th century also neglected the potential heat loss from convection. And so did other climate-related calculations through the next century.

It was only with the development of Charles Keeling’s measurements of carbon dioxide at the Mauna Loa measuring station in Hawaii in the 1960s that it inspired more concern and additional research.

But even with that additional data, the science wasn’t confirmed as there were still questions about how much was affected by the carbon cycle and how much carbon dioxide came from natural sources, how much would be absorbed by the oceans, how much heat would be absorbed by water vapor in the atmosphere, and how much heat could be absorbed by carbon dioxide.

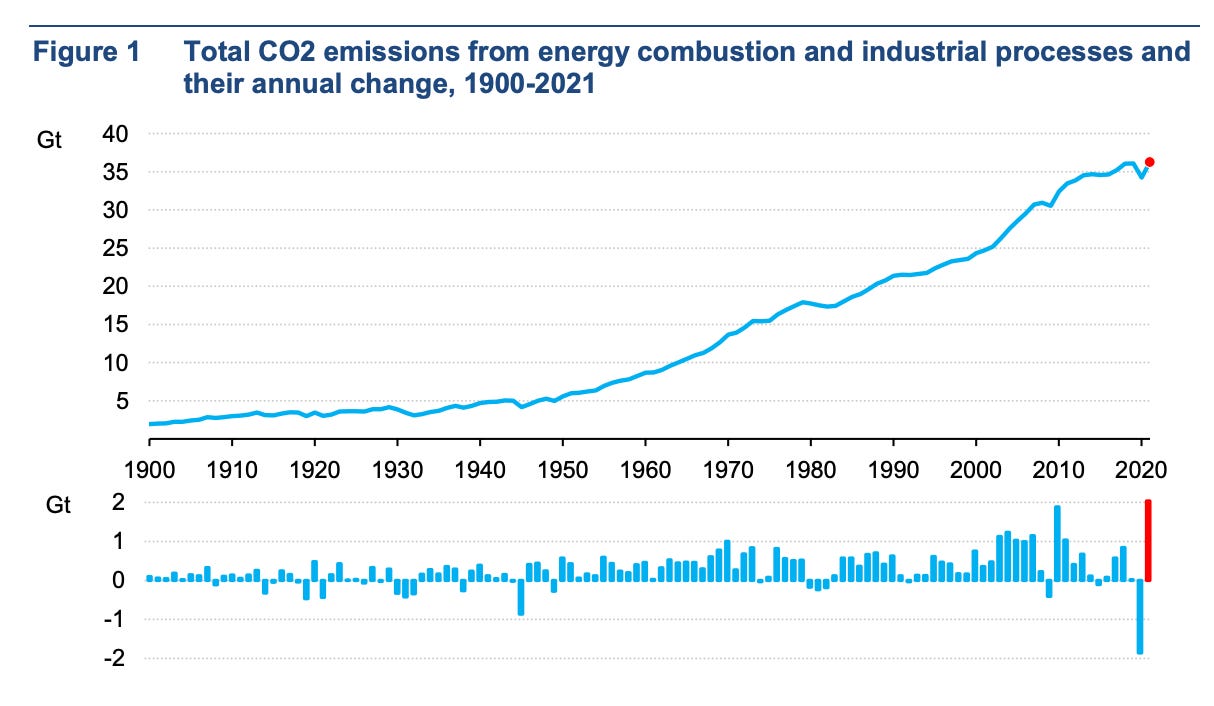

What may be the most damning evidence against the theory is that no perceptible change in temperature or carbon dioxide levels have followed the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the International Energy Agency, carbon dioxide emissions related to energy consumption declined by 1.9 gigatons in 2020 as gasoline consumption collapsed.

NOAA has a special page dedicated to addressing this topic written in 2021, detailing potential complications from the carbon cycle and the possibility that the change might take some time to be reflected in temperature measurements, not less than a year. But three years since the pandemic and no noticeable drop has yet been seen.

An interactive climate model produced by the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR)—a national coalition of universities focused on climate research and funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF)—shows temperature moving in annual lockstep with changes in carbon dioxide—not a one or two year delay.

Even if the carbon cycle might obscure changes in carbon dioxide emissions, other greenhouse gases like methane and nitrous oxide have also not seen any kind of decline as a result of the pandemic.