Not Just Three Mile Island: Low Demand, Interest Rates Killed Nuclear Power's Heyday

From the late 1960s to the early half of the 1970s, nuclear power was growing by leaps and bounds in the United States. As the technology developed, more and more plants were approved for permits to keep up with growing energy demand. Between 1967 and 1977, 92 reactors were given operating permits according to Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) data.

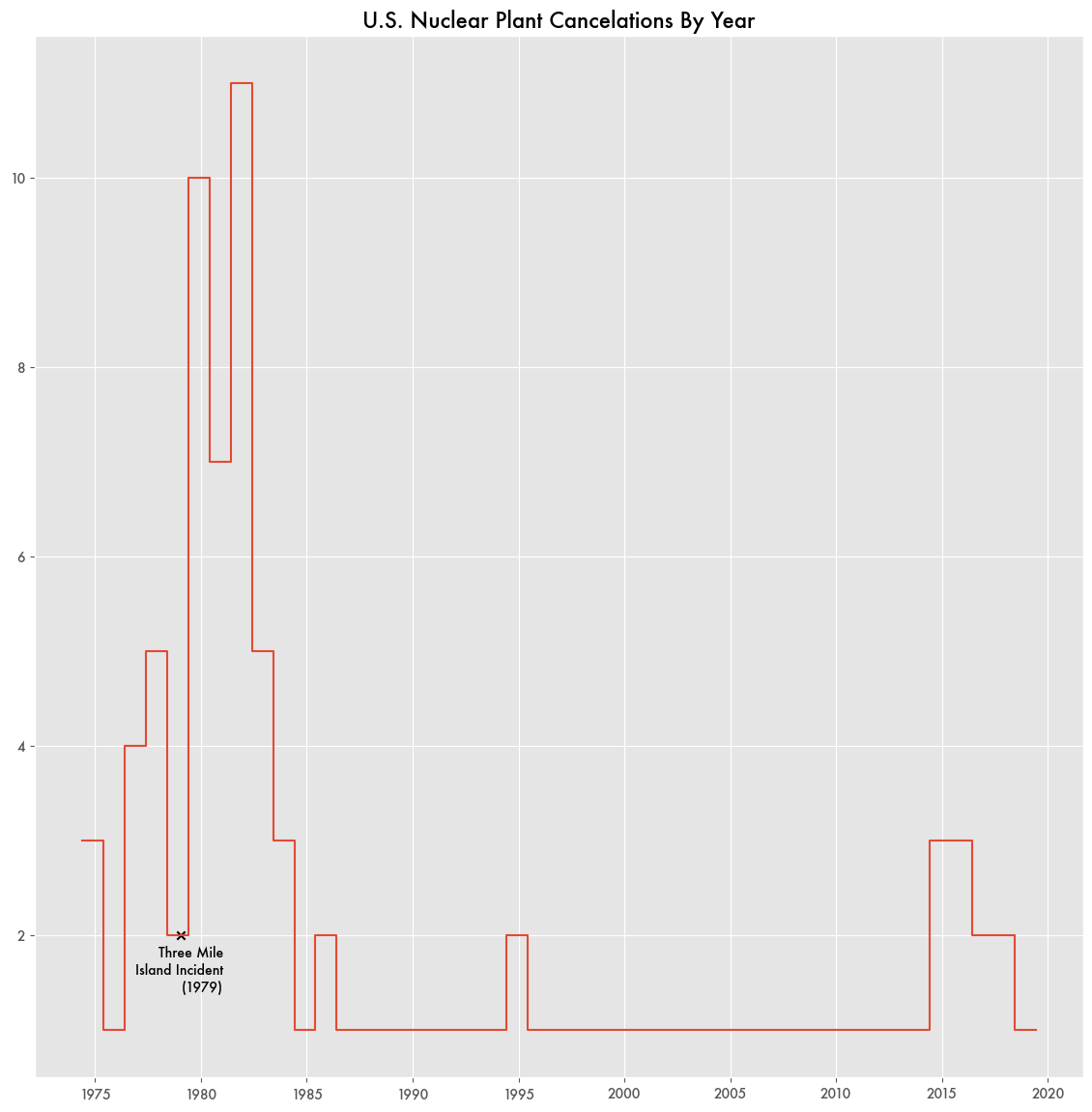

That all came to a sudden halt in the late seventies. No nuclear plant would seek a new permit until the mid-2000s. While some plants already approved would still be constructed in the following years, many already approved plants would be canceled.

The common explanation is that the partial meltdown incident at Three Mile Island in 1979 scared off public support for nuclear power. The threat of a catastrophe near Philadelphia, combined with anti-nuclear environmental protests and the release of the movie The China Syndrome a week later—about an almost nuclear catastrophe eerily similar to Three Mile—stopped any demand for nuclear power.

The NRC immediately enacted a one year moratorium on nuclear permits. Nuclear safety regulations were increased, leading to further permitting delays, and power companies entered into new insurance pools to cover potential accidents. Besides the protests and class-action lawsuits surrounding Three Mile Island itself, anti-nuclear sentiment from environmental activists became more heated nationwide, which led to protests, concerts, federal and state litigation, and testimony against upcoming nuclear projects. The combined cost and burden of building a nuclear plant became seemingly untenable.

Proposed plants in Bailly, Indiana, Marble Hill, Indiana, Erie, Ohio, and Midland, Michigan would be abandoned over citizen opposition, lawsuits, and delays.

While Ohio Edison stood by the safety of nuclear energy, delays meant the project was dead in the water:

“The political and regulatory uncertainties affecting the future construction of nuclear plants has intensified following the accident at Three Mile Island. Nuclear construction scheduled in the future carries greater uncertainty of eventual cost.”

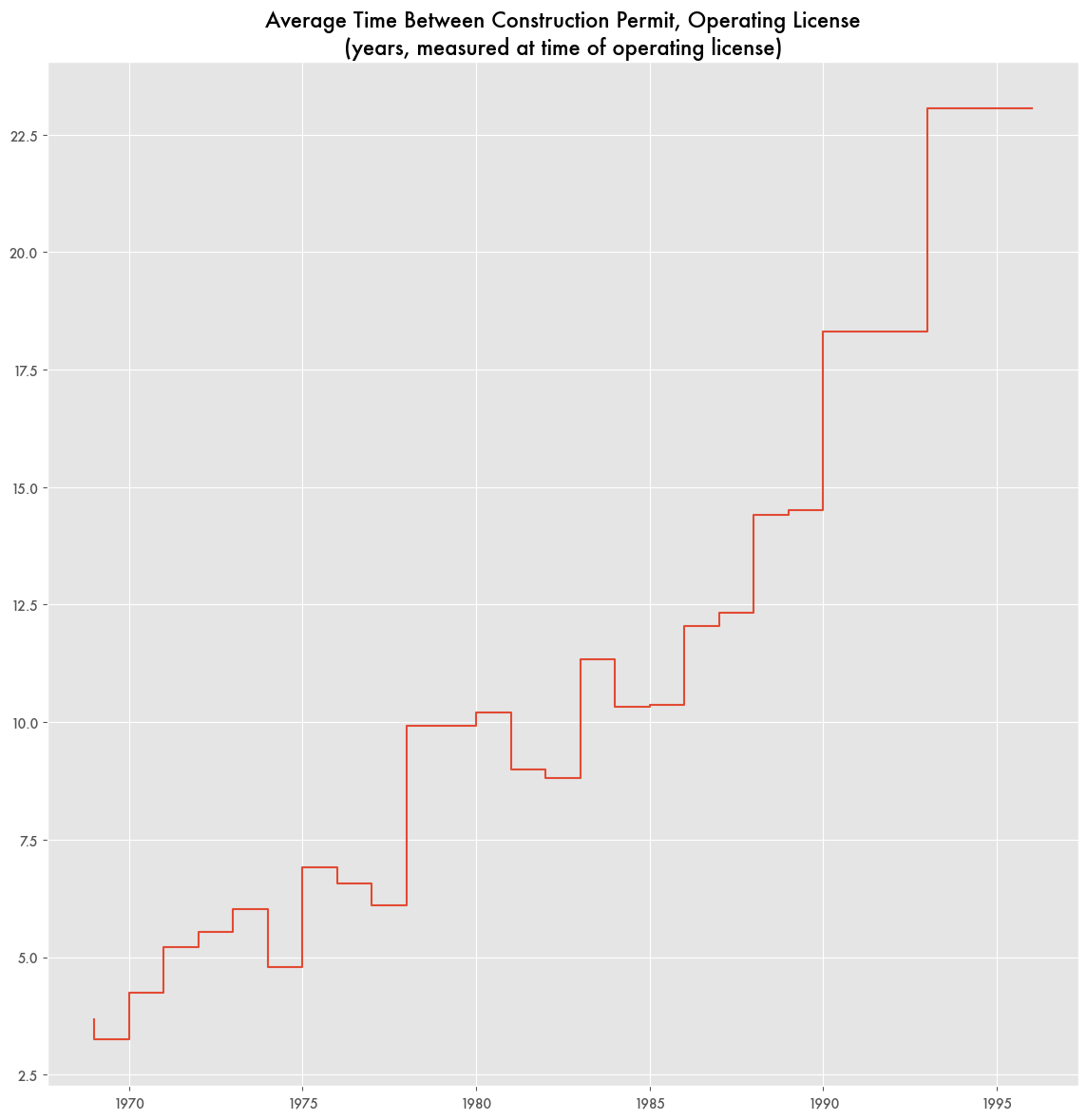

Three Mile Island certainly did delay nuclear construction, but construction times for nuclear plants were already growing year over year for the last decade. Changing technology and changing standards for first-of-a-kind projects meant more difficulties in building a nuclear plant—something inherent in many nuclear energy projects that continues to this day.

In 1970, average time between construction permit and operating license was 3.2 years based on NRC operating reactor data. By 1978, it was 6.7 years. By 1988, it was 12.3 years.

More Than Just Three Mile Island

Anti-nuclear sentiment and regulations alone wouldn’t completely explain why projects that had already been permitted were canceled. While 36 projects would be canceled within a few years after it happened, nine proposed plants were canceled in the two years before the incident.

Oil Crisis, Interest Rates, Recession, and Declining Energy Demand

Not just anti-nuclear sentiment and regulations, lack of demand and financial concerns were also significant issues.

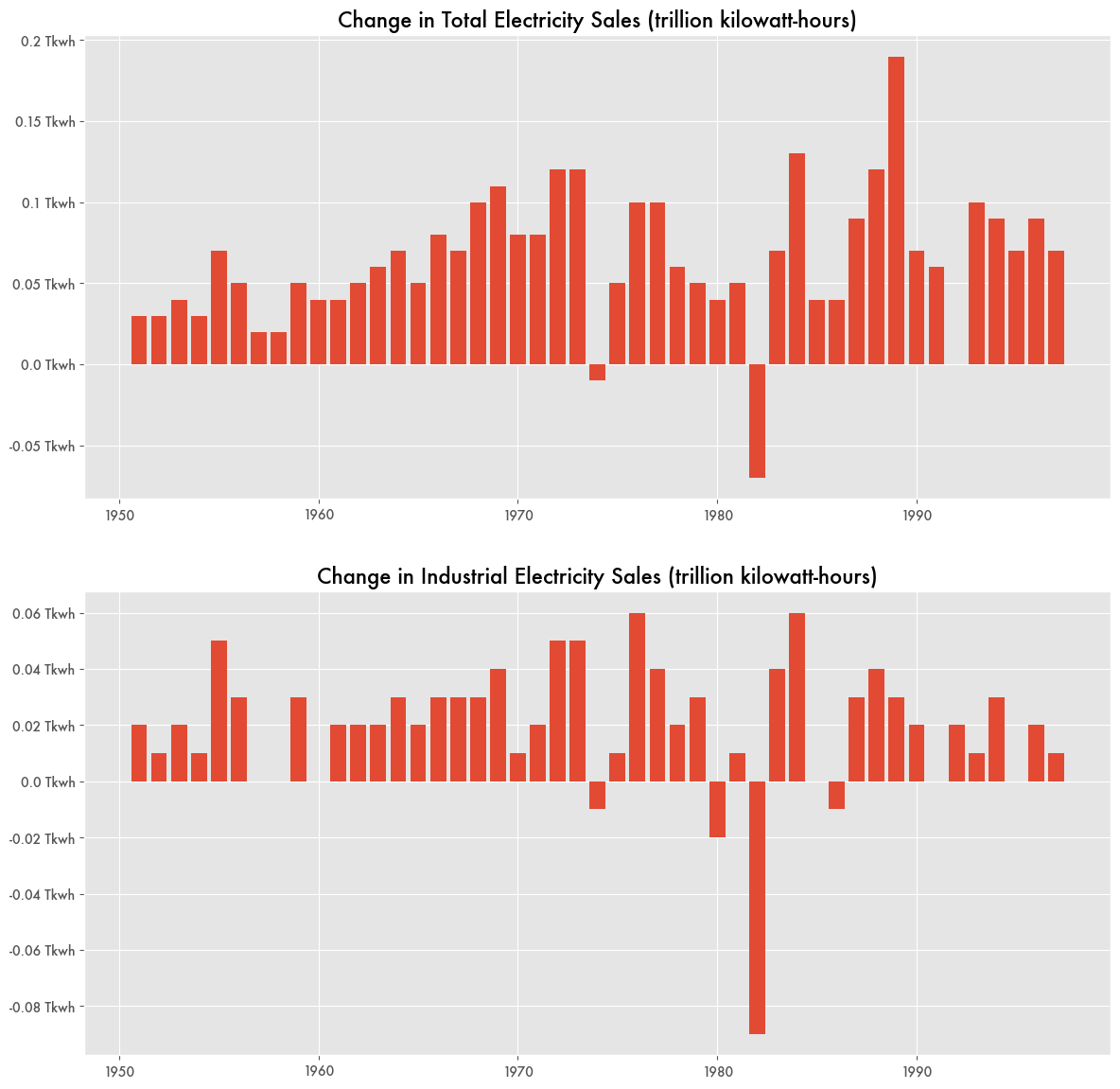

While oil and gas prices spiked after the 1973 oil crisis, potentially making nuclear power a cheaper option for electricity generation, high prices also meant a drop in electricity consumption, particularly for the industrial sector, which is unlikely to produce as much when prices are high.

That drop was even more severe in 1979 during the second oil crisis. High oil and gas prices limited industrial output and industrial electricity consumption along with it. When combined with historically high interest rates driven by Paul Volcker and the Federal Reserve’s attempts to wring out inflation from the economy and the ensuing recession, 1982 would be the largest single year decline in industrial electricity sales—tied with the financial crisis in 2009. High interest rates would also hamper any nuclear project leaning heavily on borrowed money for their funding.

Altogether, the original reason to build a nuclear plant to satisfy increasing energy demands was not there, more difficult to justify financially, and much of the planned nuclear capacity was no longer necessary.

For example, the Montague nuclear plant was planned to be a 1.1 gigawatt nuclear reactor in Montague, Massachusetts permitted for construction in 1973. It saw continuous protests throughout the 1970s led by Sam Lovejoy, a figurehead in the anti-nuclear movement who would go on to help found Musicians for Safe Energy (MUSE). MUSE would organize high profile anti-nuclear concerts with the likes of Bonnie Raitt, Graham Nash, and the Doobie Brothers.

The plant was eventually canceled in 1981 after $23 million had already been spent and nothing to show for it, not because of anti-nuclear sentiment but because the region no longer needed the extra capacity.

The Illinois Power Company canceled its plans for the Clinton 2 nuclear plant in 1985 as any unserved demand would likely be met with the Clinton 1 plant already in construction and in operation in 1987.

The Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO), now known as Dominion Energy, stood by the potential for nuclear energy in 1980 despite the downturn in demand, the licensing moratorium, extensive emergency drills, and increased safety regulations to open their North Anna 2 power station in 1980—the first licensed plant after Three Mile Island—but they would cancel plans for North Anna 4 and severely delay plans for North Anna 3.

A proposed nuclear plant in Forked River, New Jersey had been on the edge of survival for some time because of financial struggles following public opposition and declining energy consumption from the first oil crisis in 1973. Once Three Mile Island happened and interest rates shot up, its cancellation was all but guaranteed.