Ramaswamy's Biotech Firm's Clinical Trial Reinterpretation

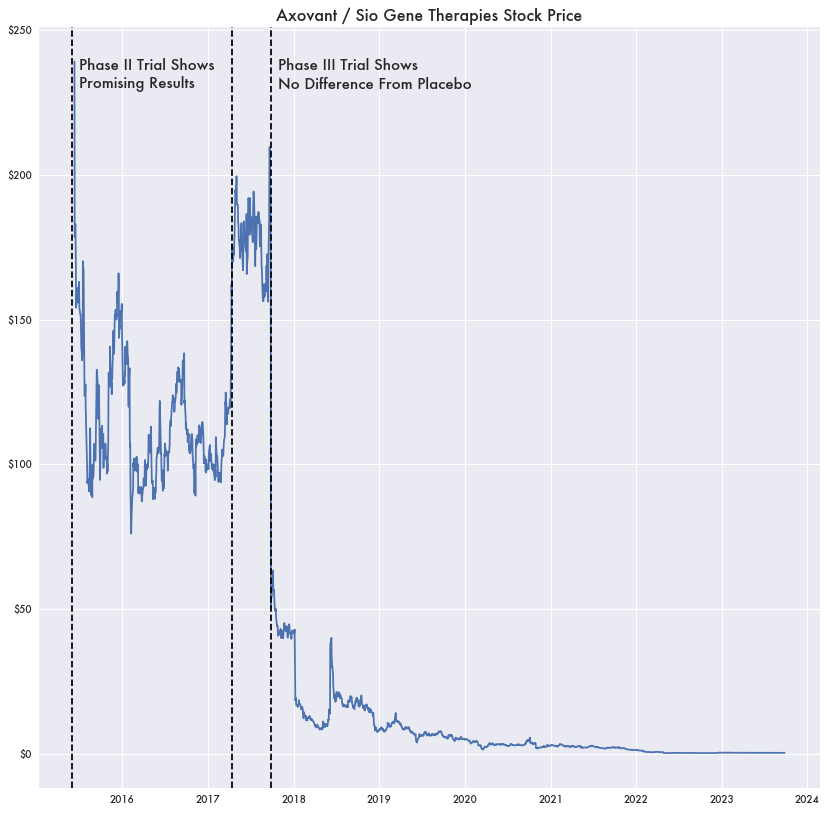

Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy was previously the head of a biotech firm, Axovant Sciences. During the course of his campaign he has been criticized for using the firm to pump up the company’s stock surrounding an ineffective Alzheimer’s drug treatment before cashing out.

Ramaswamy has defended his biotech career, stating that most drugs aren’t successful, particularly those for Alzheimer’s disease, and the drug, intepirdine or RVT-101, was simply one of them. An article in Forbes on Ramaswamy’s approach described it as identifying potential hidden gems using data and a keen eye for outliers.

But the company wasn’t able to enter the stock market with an IPO in the billions because of a gamble on an unproven drug and data analysis; it was based on presenting a previous failed phase II clinical trial as a successful drug, justifying a phase III clinical trial. The results were published in the Alzheimer’s & Dementia journal with no mention that it was based on a prior trial that showed no significant benefit.

Some at the time were skeptical of Axovant’s ascent and said so publicly. FierceBiotech published a story describing Axovant as a company that leapt onto the market with over $1 billion in value despite having “no track record, no experience and one questionable product.”

According to the Axovant study, a combination of Alzheimer’s-specific improvement metrics—such as ADAS-cog, ADCS-ADL, and CDR-SB—was better for participants that took the drug versus those that didn’t at various points in the study. But based on Axovant’s own application for the phase III study, there was no significant difference at the 48 week mark—the end of the study—while other individual metrics showed no significant improvement.

There was no statistically significant effect of RVT-101 on RBANS for either dose over placebo, but some degree of separation did appear at later visits for the 35-mg group. No statistically significant difference for either group was seen on the MMSE at Weeks 24 or 48.

One part of the metric touted in the study—CDR-SB or Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes—appears to show no benefit at any point by itself.

Adverse events and serious adverse events were higher for those who took the drug (61.9 percent and 11.4 percent) versus those that didn’t (55.6 percent and 7.6 percent).

Somehow the drug went from abandoned by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) after numerous failed trials to a potential blockbuster following the reinterpretation of a phase II trial with Vivek’s mother as one of the researchers. When it got to the phase III trial, the results showed no significant difference between the drug and placebo—similar to that of the GSK trials.

Most drugs seeking Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval go through the three phases—the first to test for safety, the second to test for general effectiveness, and the third to compare against placebo and other alternatives. A double-blind phase III trial is the gold standard of testing, and usually these trials will be registered with ClinicalTrials.gov and have a substantial number of participants.

Running a phase III trial is usually expensive and time intensive, so the process is usually only reserved for drugs that have shown enough promise to warrant it. For intepirdine, its numerous prior failures would not have justified a phase III trial, which is why GSK sold it for a measly $5 million to Axovant—a meager sum in the world of pharmaceutical drugs.

Axovant would eventually rebrand as Sio Gene Therapies, and would liquidate in April of 2023.