Tax Credits For Solar Energy That Can't Be Produced

The investment tax credit (ITC) and the production tax credit (PTC) are two major subsidies for renewable energy generation in the U.S. via the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The PTC provides a federal tax credit for every kilowatt-hour of renewable energy generated for the first ten years of generation, while the ITC provides a credit for every dollar invested in a renewable energy source.

For the most part, the ITC credit is used mainly for solar energy, while the PTC is used mainly for wind but also for various other sources like biomass, geothermal, and certain types of hydropower. The PTC credit has varied anywhere from .3 cents to 2.9 cents per kilowatt-hour based on which year it was applied for and what type of energy was being used. For the ITC, it has regularly been based on 30 percent of the amount invested.

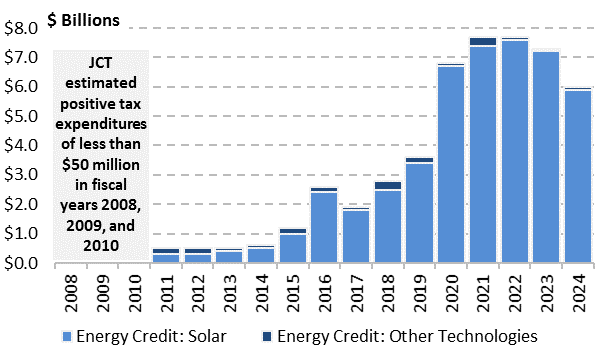

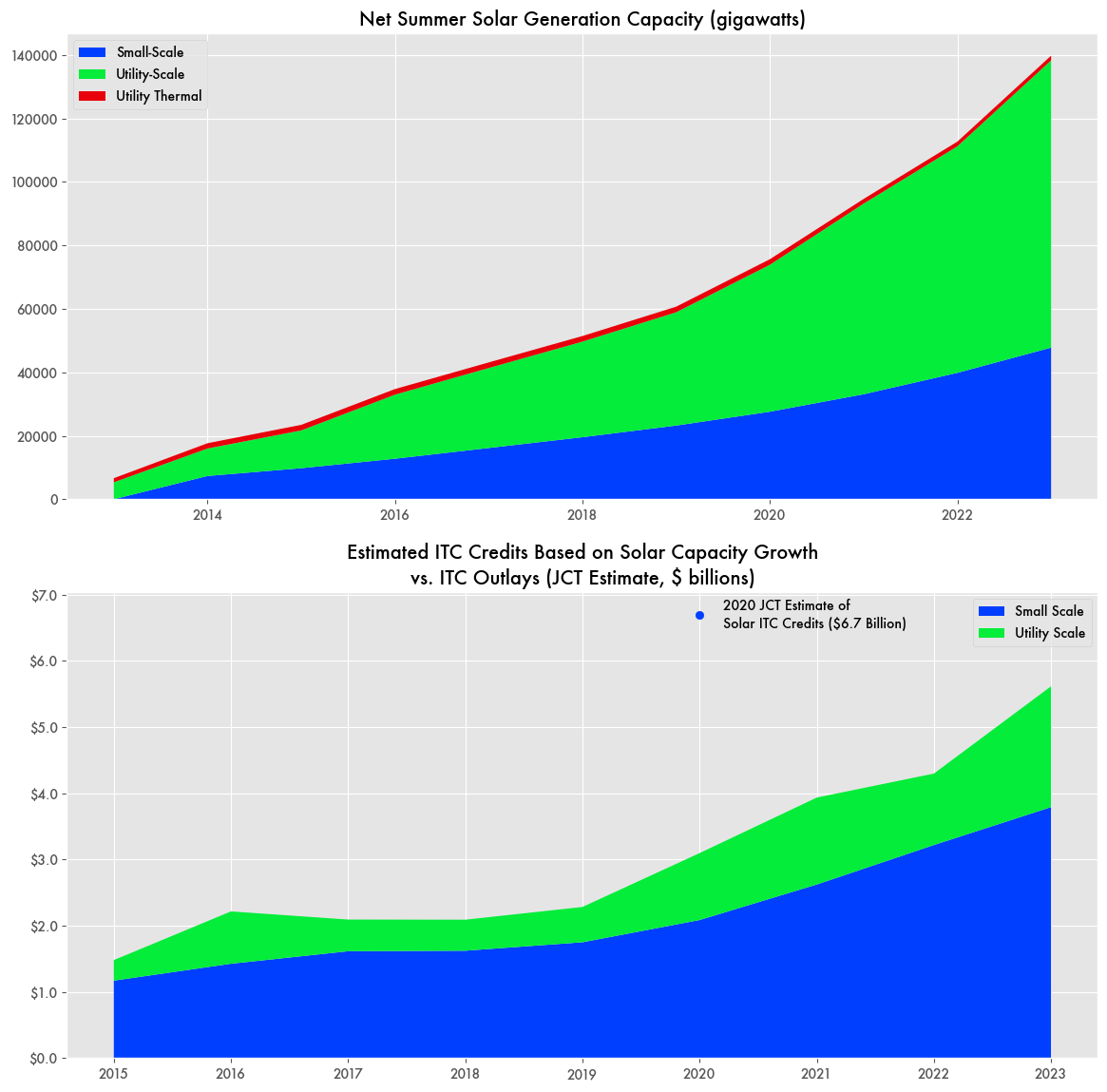

The fast growth and large investment in renewable energy generation has meant a large reliance on the ITC credits. According to Energy Information Administration (EIA) data, net summer solar generation capacity in the U.S. went from under 7 gigawatts in 2014 to almost 140 gigawatts in 2023. The amount of qualifying ITC credits followed in suit, going from less than half a billion to over $7 billion in 2022 according to a Congressional Research Service (CRS) report from 2021.

But the large growth in solar capacity doesn’t justify the amounts being claimed for ITC credits.

For example, EIA data on solar generation capacity shows a growth of 11.3 gigawatts between 2021 and 2022. At an average solar construction cost of $1,590 dollars per kilowatt-hour, based on estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), that would equate to $17.97 billion dollars invested in solar. CBO estimated a similar $17.01 billion invested that year. Thirty percent of that would be slightly over $5 billion—significantly less than the over $7 billion claimed in ITC credits that year based on the CRS report.

And the large growth in solar capacity is largely driven by utility-scale solar—commonly defined as over 1 megawatt of capacity, like those seen on solar farms—and utility-scale solar doesn’t get the full 30 percent credit but instead a base 6 percent credit. Based on that 6 percent rate, the probable ITC credits available would be even further below the $7 billion spent on the program for solar.

Instead, about 35 percent of capacity in 2022 came from small-scale solar. Using that same CBO-estimated construction cost rate for 2022 ($1,590 dollars per kilowatt-hour), that works out to $4.3 billion in ITC credits ($3.2 billion for small scale solar and $1.1 billion for utility-scale).

ITC Costs Could Be Even Higher

The numbers on ITC credits published in that CRS report are based on information from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT)—a subdivision of Congress, similar to the CBO, that provides analysis on taxation matters.

But those JCT numbers are only estimates. The IRS doesn’t provide statistics on ITC credits, and there is some ancillary evidence that the cost of the ITC program could be significantly higher than what the JCT estimated.

In a similar report on the PTC credit system, the JCT estimated the cost of the program for 2015 at $2.6 billion, while the IRS provided numbers of a much higher $4 billion.

Previous Abuse of ITC Credit Loophole

ITC credits were also at the heart of a major Ponzi scheme and bankruptcy known as DC Solar.

DC Solar was a California startup created in 2007 by a local mechanic that developed portable solar arrays. It grew quickly, gained national attention and investment from the likes of Warren Buffet, and picked up multimillion dollar contracts from large companies like Sherwin-Williams.

While the company was developing a potentially viable product, a large portion of their profits came from the ITC credits that came with investment in renewable energy. But there was no guarantee that the money invested in portable solar panels actually went to producing energy, but simply just to ITC credits.

But it wasn’t the use of ITC credits that made it run afoul of the law, but its turn to a Ponzi-like scheme involving accounting manipulation where early investors were paid off with later investors’ money.