The Bias in Post-Pandemic Autism Analysis

In April, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) announced the estimated prevalence of autism is now 1 in 31 for those aged 8 years old in the U.S. That works out to be over 32 people per 100,000, or 3.2 percent.

While that is thirty times higher than what it was in the 1990s, those numbers are skewed by significant changes in the definition of autism over the last two decades and the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which includes other conditions like Asperger’s.

But even since the inclusion of ASD in the DSM V in 2013, the rate has gone up significantly, mainly since the pandemic. It was 1 in 44 in 2018, and by 2023 it was 1 in 36.

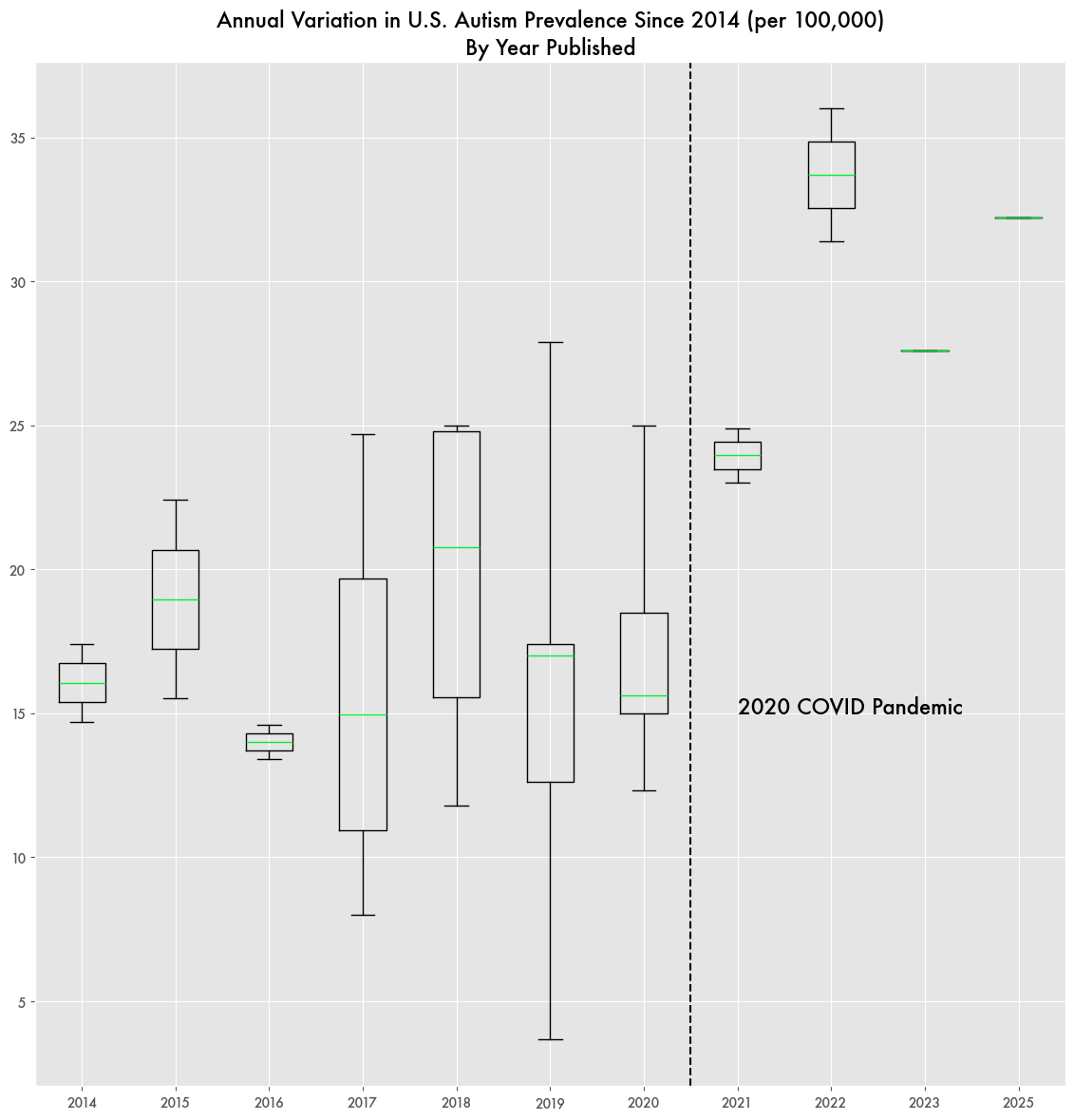

In the years between the 2013 release of the DSM V and the pandemic, autism prevalence didn’t vary much across studies in the U.S. and was surprisingly consistent for a syndrome associated with an epidemic. Of the studies tracked by the CDC, only one in that period had a prevalence over 25 per 100,000. Most averaged between 15 and 20.

But after 2020, the lowest prevalence was 23 per 100,000. Of the studies published in 2022, none had a prevalence below 30.

While there was little difference in ASD prevalence for groups studied before the pandemic (2015-2017 vs. 2018-2020, p-value=.63802), there is a significant one compared to those after the pandemic (2018-2020 vs. 2021-2024, p-value=.00095).

Data From Before the Pandemic, But Published After

That change might hint at some effect of the pandemic and home schooling on adolescent development, but the studies published after the pandemic were largely based on research done before the pandemic. Of the studies listed in the CDC dataset, only one involved data collected after 2020.

There was also an update to the DSM V made in 2022—the DSM V-TR—that changed some criteria for autism, but the changes were relatively minor and if anything made diagnosing the condition stricter and would ostensibly lead to fewer diagnoses.

Biases Inherent in Autism Reporting

Besides the condition definitions, there are many other potential reporting biases in tracking ASD. Disability enrollment through school systems is a large source of autism data and a potential source of reporting bias. One study from California noted declining prevalence, not due to declining incidence, but because wealthier parents were now more likely to opt out of the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS) in favor of private care, and therefore those children with ASD were not getting tracked.

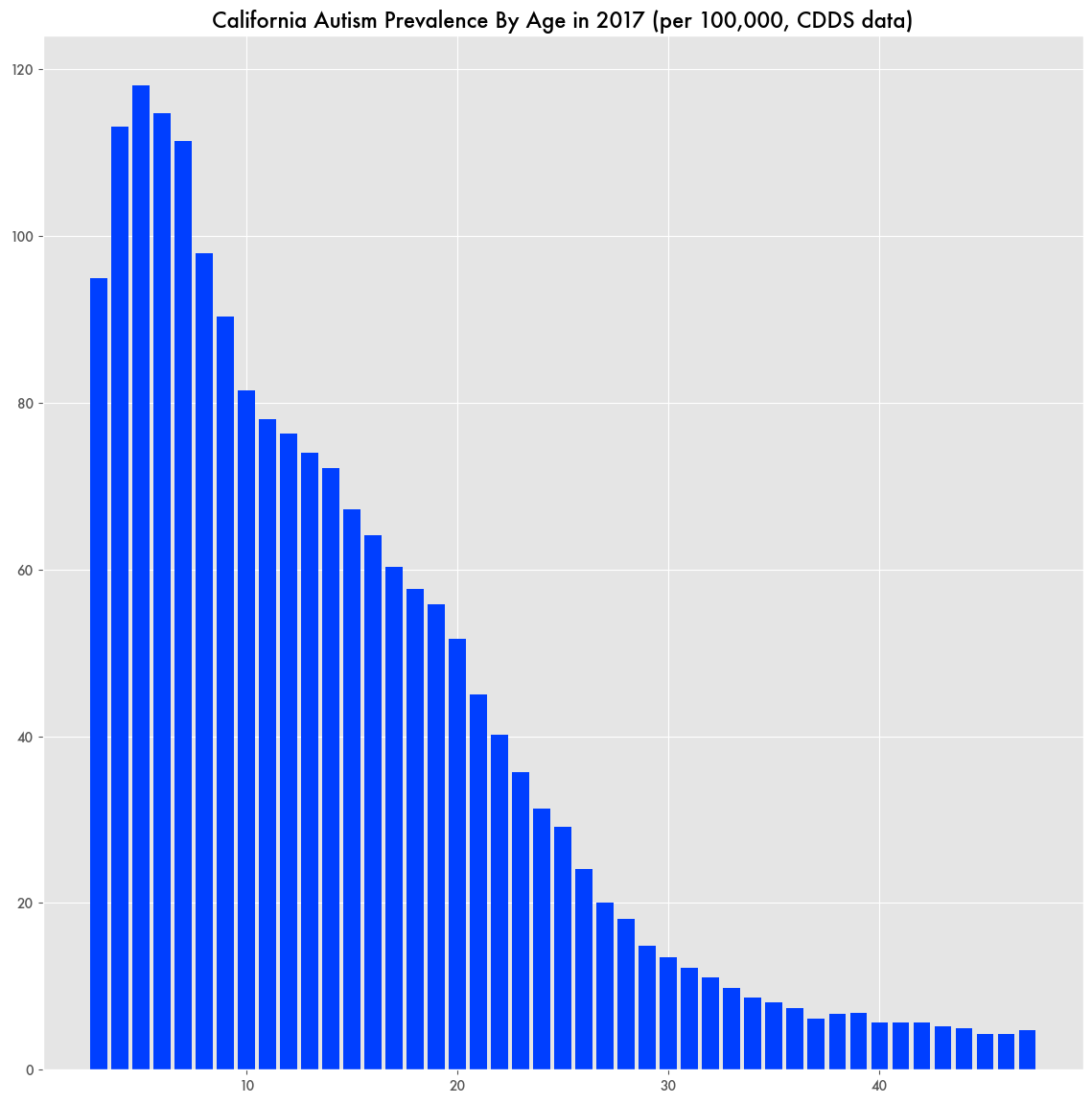

Different studies vary by the age of study enrollees, which can alter the results as autism counts vary significantly with age. Prevalence peaks at age 7, declining for every age after and dropping off substantially at 10 and 21 based on California DDS data.