The Large Spreads and Negative Pricing in Energy Congestion Markets

A common criticism of wind power is that the large subsidies given to the industry help drive down bid prices for electricity to the point where prices can go negative, skewing market values.

Those subsidies, combined with excess capacity when the wind is blowing more than expected, means that generators can give away their electricity at bargain basement prices or even pay other utilities to take it off their hands.

But slightly negative prices for power generation are nothing compared to what happens in congestion auctions. Based on data from the mid-Atlantic regional transmission operator (RTO) PJM Interconnection, congestion bid prices are not just regularly dipping a toe into slightly negative values; they are consistently negative.

Over 36 percent of energy bids in the financial transmission rights auctions for the month of September between 2006 and 2020 were negative. Sometimes prices dipped as low as -$999,990 per megawatt.

These bids are not the final price paid for the electricity, but for derivative bids on congestion pricing—effectively a bet on whether there is too much or too little energy for the grid at that time.

Yet they give a glimpse into how complex energy markets are currently operating. The auction process is driving bids lower and lower to earn the opportunity to sell higher at a later price (73 percent of negative bids are for buys rather than sells).

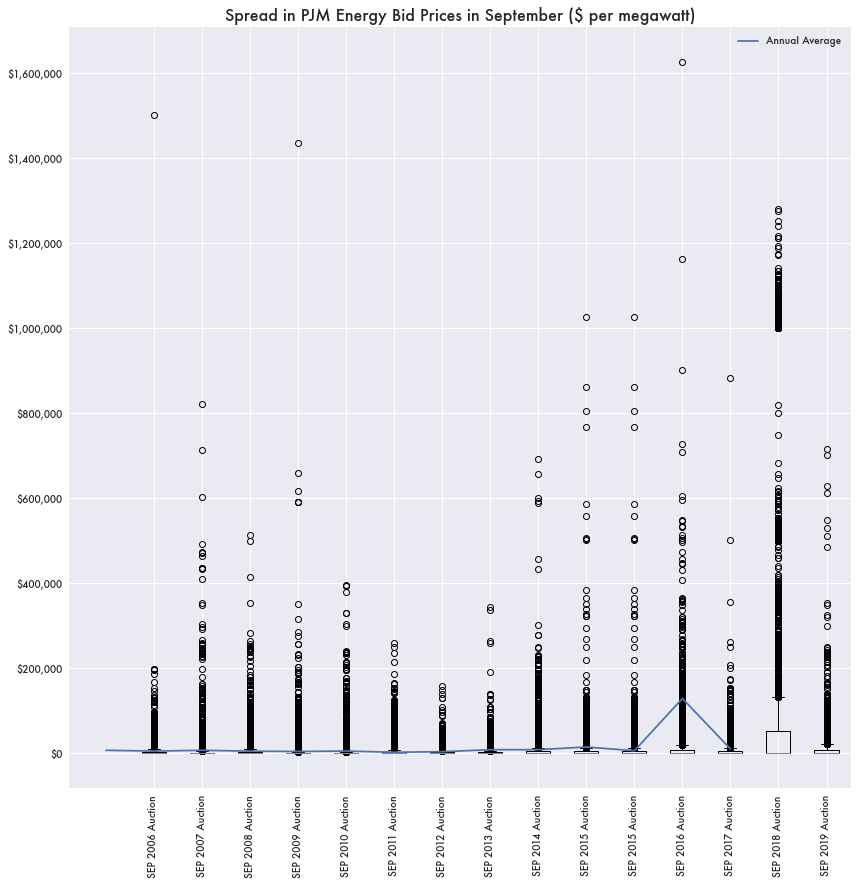

An estimated spread in price per megawatt—the difference between the minimum bid and the maximum bid within that month at that node—can rise above $1 million per megawatt.

While these markets are meant to add liquidity and help balance the costs of power transmission, the end result is questionable. Despite all the negative pricing in power auctions, the subsidies for renewables, and the shale revolution driving natural gas prices cheaper and cheaper, electricity prices are only getting more expensive and congestion prices keep going up.

The average wholesale cost of electricity in PJM was $63.97 per megawatt-hour in 2021 based on annual reports. In 2002, it was $28.30 ($42.03 in 2021 dollars). Average retail revenue for the Potomac Edison Power Company (PEPCO)—a major utility for the D.C-Maryland-Virginia region and within PJM’s energy market—went from $71.59 per megawatt-hour in 2002 to $120.10 in 2022.

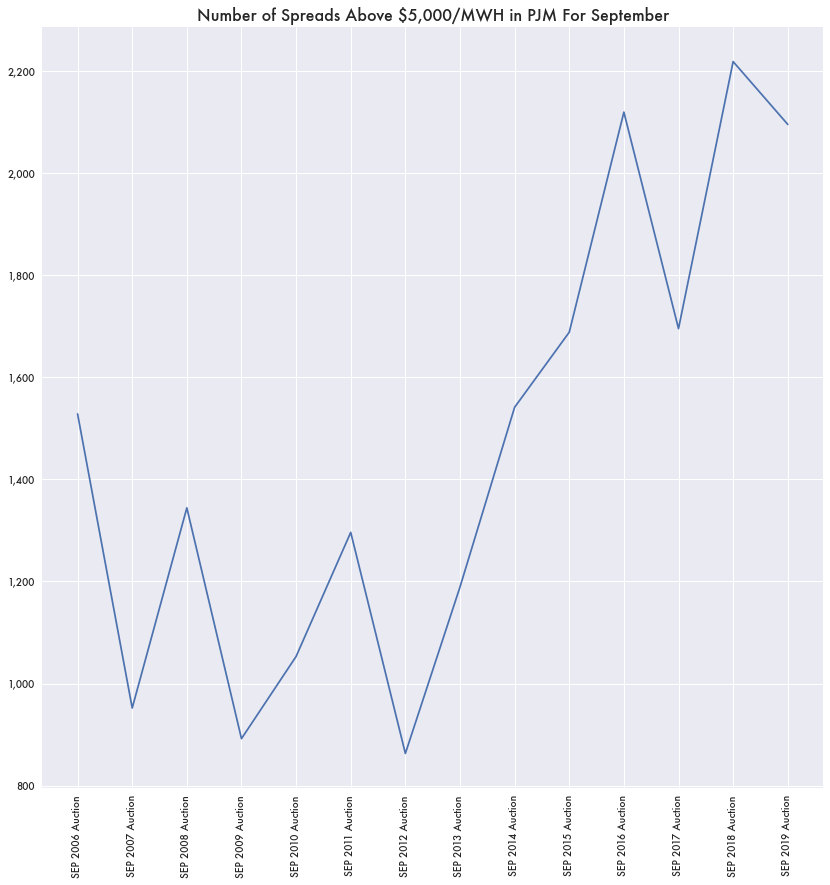

Growth in Spreads Since Negative Pricing Allowed For Wind

Not only are some of the spreads incredibly high, but they are trending higher. The number of spreads above $5,000 per megawatt has steadily increased since 2012. That has followed the growth of renewables in PJM’s generation mix, which in 2010 represented less than 2 percent of generation and is now at 10 percent according to Monitoring Analytics.

That 2010 report also details how PJM first allowed negative pricing in 2009 and only for wind units. The growth of solar and wind energy generation has also added more volatility into energy generation as they are both considered intermittent sources—they don’t work when the wind stops blowing and the sun goes down or gets covered by clouds.

In PJM, wind only represents around 1 to 2 percent of generation capacity. Total renewables account for less than 10 percent. The larger majority of generation comes from natural gas.

PJM is one of the few RTOs that tries to account for generation issues through various bidding markets. They operate separate capacity auctions—where market participants can offer energy generation bids far in advance of the day-ahead auctions—to balance the growth of intermittent generation in favor of consistent baseload generation like coal, hydro, and nuclear.

The Massive Spreads in 2018

Overall, congestion bid price spreads don’t change much from year to year, except in 2018. That year saw a massive decline in the average bid price as well as the minimum bid price, but not the maximum bids.

For whatever reason, that year led auction participants to underbid by hundreds of thousands of dollars per megawatt.

Note: A previous version of this story included an incorrect detail about congestion prices. Congestion prices have decreased over time, while wholesale prices have increased.