The Negligible Effect of Russian Sanctions

Following the start of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, Europe, the U.S., and other G7 nations instituted sanctions on Russia such as a ban on purchases of Russian oil and gas, price caps on Russian oil, and a ban on insurance for freighters carrying Russian oil.

According to various reports, the sanctions were crippling the country. A February 2023 Financial Times story described Russia’s deficit as soaring because of slumping energy revenues.

The Atlantic Council—an international affairs think tank that is heavily supportive of Ukraine and maintains a database focused on Russian sanctions—said sanctions were very effective. According to a story on their site, Russia’s oil and gas revenues were down 46 percent year-over-year as of February of 2023, squeezing the Russian economy and depressing industrial output. Without access to freight insurance from the West, Russian shippers were forced to export oil via Indian and Chinese barges.

But a more recent Financial Times story detailed how Russia was regularly dodging the price cap set on its oil exports. Based on Urals spot price data, Russia likely earned more money in oil revenues from higher prices in 2022 than 2021, not less.

Large Spread But High Prices

Sanctions may be keeping Russian oil trading below current oil prices, but that may not mean much.

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, the Urals crude oil benchmark—the price that Russian oil usually trades at—has traded below other international benchmarks like Brent crude or West Texas Intermediate according to International Energy Agency (IEA) data.

Oil prices had been steadily increasing since the collapse in prices during the pandemic. Once full-on war broke out in January of 2022, prices paid at the Urals benchmark would diverge from that of Brent. Sanctions on Russia implemented in March of 2022 would ostensibly send Brent oil prices to almost $140 a barrel and the spread between the two benchmarks would go from $5 a barrel to $30 to $35 a barrel.

While the spike in prices would fade in the second half of 2022 as President Biden released additional oil from the strategic petroleum reserve according to analysis from Energy Information Administration (EIA), the massive spread between the two benchmarks remained.

Yet while Russian oil was trading below that of other countries, Russia was unlikely suffering because oil prices were still high.

According to annual averages from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) Annual Statistical Bulletin, Urals benchmark prices in 2022 reached nearly $80 per barrel on average—the highest it had been since 2014.

Little Change in Russian Oil Production And Exports

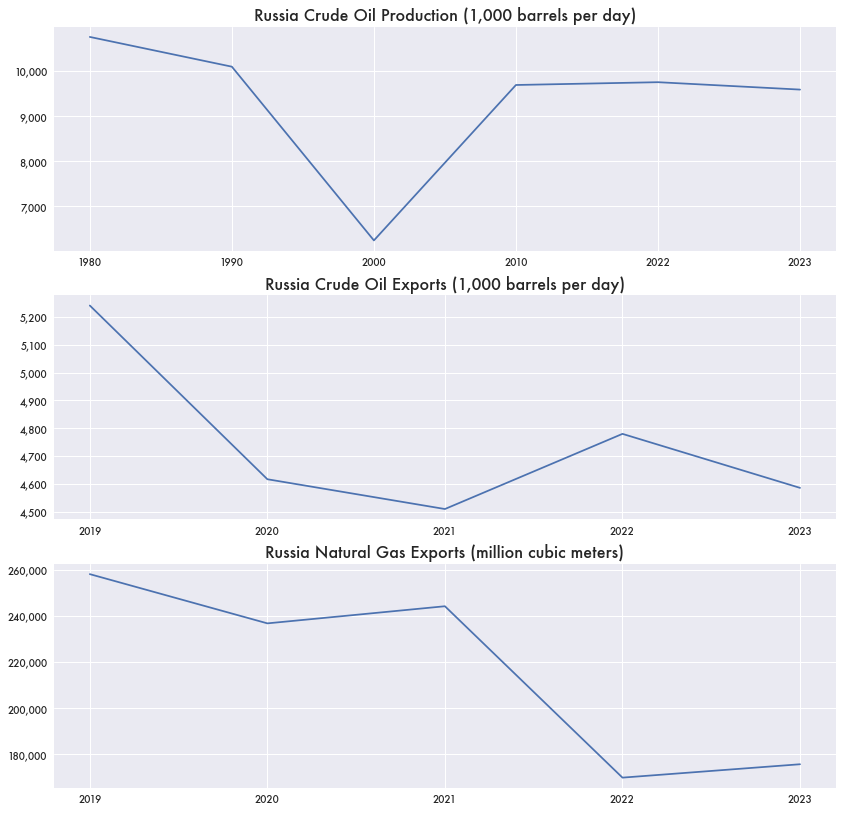

Besides prices, sanctions haven’t really affected oil and gas production or export volumes either. Crude oil production is effectively where it was ten years prior. Russian oil exports are higher than they were in 2020.

More Revenue From Fewer Natural Gas Exports

Only natural gas exports saw any appreciable decline in 2022—from 258,000 million cubic meters a year to 176,000. But natural gas prices were so extremely high at the time because of the war that there was likely no need to export as much.

Russian gas prices reached over $70 per million British thermal units (BTUs) in August of 2022—easily over ten times the average price prior to 2021. If Russian gas prices had only doubled, it would still lead to Russia earning more revenues than prior years with diminished exports.

Large Spreads Benefit The Middlemen

While the $30 spread in the Brent-Urals benchmarks is not breaking Russia’s economy, it does potentially mean billions not earned by Russian oil producers annually, likely to the benefit of middlemen—oil traders that can buy in one location and ship to another where prices are higher.

China infamously buys cheap, sanctioned, Venezuelan oil for its own imports and to resell on world markets at a higher price. As sanctions on the South American country were recently reimposed, China began paying less for Venezuelan oil, which would otherwise have gone to places like India.

While that loss to middlemen is likely significant, there’s no real way to know if Russia is benefitting from the spread in prices the same way that China does.