U.S.-China Trade Reporting Discrepancy Swings the Other Direction

Over the last decade, China has regularly reported over $50 billion less in exports to the U.S. than what the U.S. reports as imports from China each year.

While that gap has steadily decreased, in 2020 China actually started reporting more than what the U.S. did for the first time according to numbers from the U.S. Census, China’s General Administration of Customs, and United Nations Comtrade data.

What had been around an average $2 to $3 billion underestimate of exports by China a year ago became a $2 to $6 billion overestimate throughout most of 2020. Although the first switch appears to have occurred in November of 2019.

Brad Setser, economist for the Council on Foreign Relations and former economist with the U.S. Treasury, noted the appearance of the discrepancy earlier in October, and told Investigative Economics that the sign-shift in reporting discrepancies is largely a result of the recent China tariffs, particularly the larger set of tariffs that affects $200 billion worth of trade announced in May of 2019, but it’s not a result of other factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic or currency values.

“It’s a clear shift in the relationship between the two countries. Never has China reported more than the U.S.,” Setser said. “It’s a prima facie case for looking at how much is a result of tariff avoidance, potentially through mislabeling or misinvoicing.” Setser also noted that the current administration wasn’t prepared to deal with this when it enacted the tariffs.

Numerous factors affect accurate measurement of commodities but prior research has regularly shown trade misinvoicing as common and highly correlated with tariffs and import controls as well as trade-based money laundering.

The U.S. has seen a distinct drop in imports from China during the Trump administration and the enactment of tariffs. According to Census trade numbers for December, imports from China have dropped almost 2.5 percent per month from two years prior, over $10.7 billion worth, with a similar growth in imports from Mexico, Canada, Vietnam, and Taiwan—over $9 billion in total.

Prior Discrepancies

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) looked into the previous underestimates of Chinese imports in May and noted that the reported difference in trade surpluses between the two countries in 2019 was $55 billion—an historic low since trade exploded between the two countries over the last few decades. In 2008 it was $100 billion.

According to the CRS report, the discrepancies come from a variety of factors, including trade data reporting standards, currency exchange rates, misreporting and misinvoicing of goods to avoid tariffs, and intermediation—shipping goods from China to the U.S. via third countries to obscure their origins.

China uses Free On Board (FOB) terms to evaluate exports, and Cost, Insurance and Freight (CIF) method for imports. While the U.S. uses Free Alongside (FAS) for exports and a customs-defined metric for imports.

One ongoing issue China has been trying to clamp down on is the use of misinvoicing to move capital in or out of the country—sometimes referred to as shipping phantom goods—when currencies like the yuan get devalued or tariffs rise.

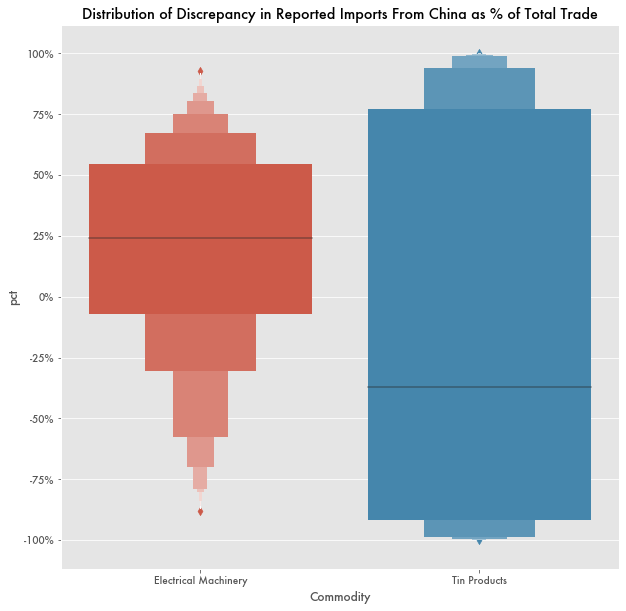

China also regularly ships exports through its Special Administrative Regions (SARs), Hong Kong and Macau. For example, in 2018, 98 percent of China's tin exports to the U.S. came from Hong Kong according to Comtrade data. For zinc products, Hong Kong shipped into mainland China 87 percent of what mainland China exported to the world.

Electronics, specifically electrical machinery, is by far the largest source of trade reporting discrepancies for the U.S. and China—almost $20 billion in 2018—solely because of the large volume of imports.

In 2018 China reported within 13 percent of what the U.S. reported, which is relatively close considering the large gap in reporting for other commodities. But for other countries that gap on electrical machinery is much smaller. For example, India’s reported electrical machinery imports from China is within half a percent on over $23 billion in goods.

Illicit Outflows

Besides tariff evasion, trade misinvoicing is often used as a tool for money laundering. According to the trade-based non-profit Global Financial Integrity, an estimated $1.08 trillion USD left China from 2002-2011, much of which ended up in New York City real estate.