What Happened to Austro-Hungarian Gold During WWI

While the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand is the spark that would lead to World War I by instigating a conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Austria-Hungary had been pushing for war with Serbia for years.

Ongoing tensions between the two countries began after the Bosnian Crisis of 1908-1909 including other assassination attempts and bombings. Even though the perpetrators of Ferdinand’s murder were arrested and prosecuted, war was all but inevitable once discussions broke down following the July Crisis without the Archduke present—the one peace supporter in the aristocracy.

Germany and Austria-Hungary would go on to form the alliance at the heart of the Axis powers, fighting against the Allies of Serbia, France, Great Britain, Russia and eventually the U.S.

Following its loss in WWI, the Treaty of Versailles would force Germany to pay a heavy toll in reparations. But while the Austro-Hungarian empire was broken up via the Treaty of St. Germain and Trianon, the successor states of Austria and Hungary paid little in reparations because they were considered destitute at the time. They borrowed heavily to fund the war through bonds—estimated to be valued at 53 billion krones at the time—much of it to pay for imported goods from Germany.

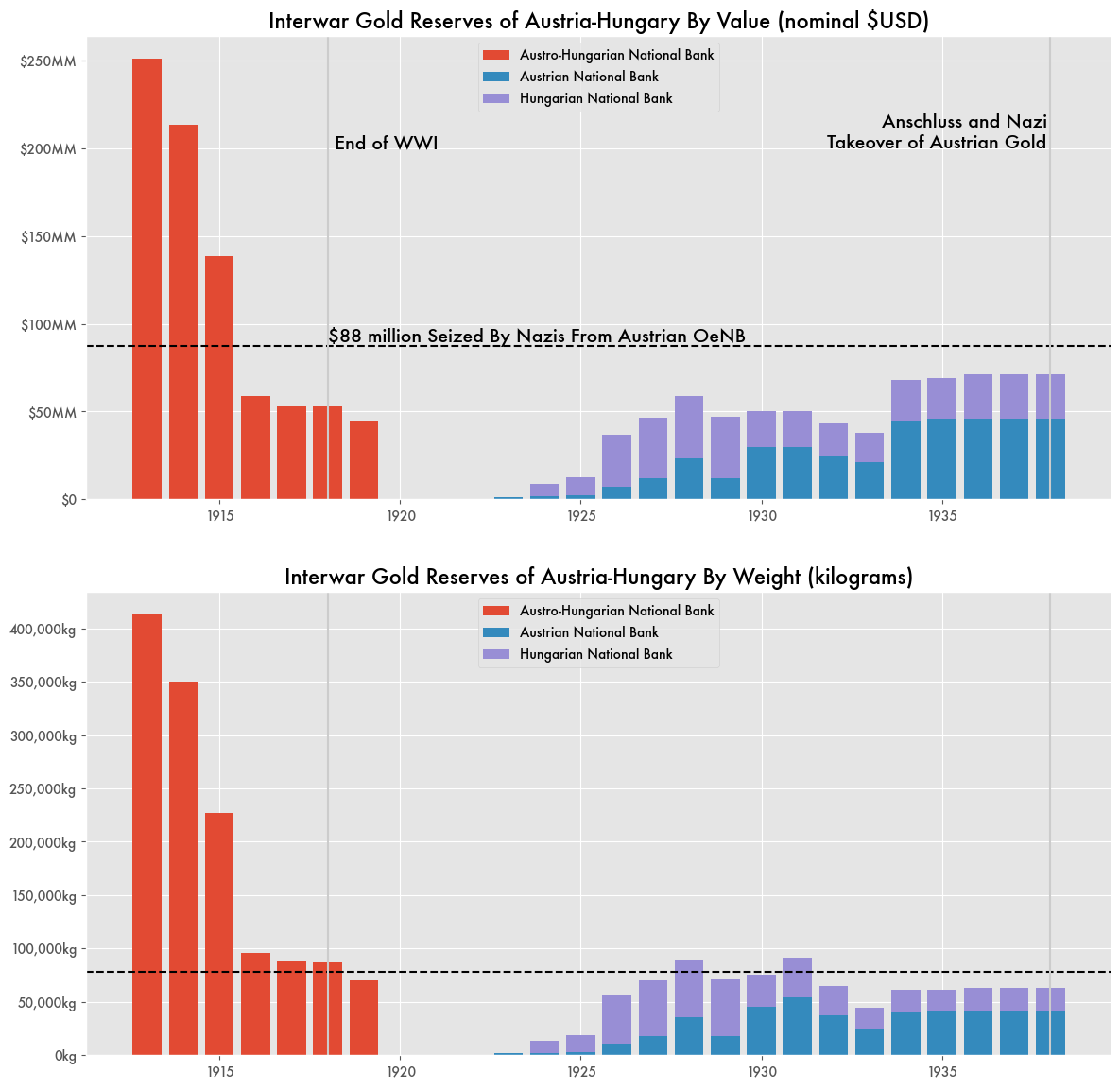

According data from the U.S. Federal Reserve, the empire’s gold reserves would fall from $251 million worth in 1913 to effectively nothing by 1922. By 1925 the now separated Austrian and Hungarian National Banks only had a combined $12 million in gold reserves.

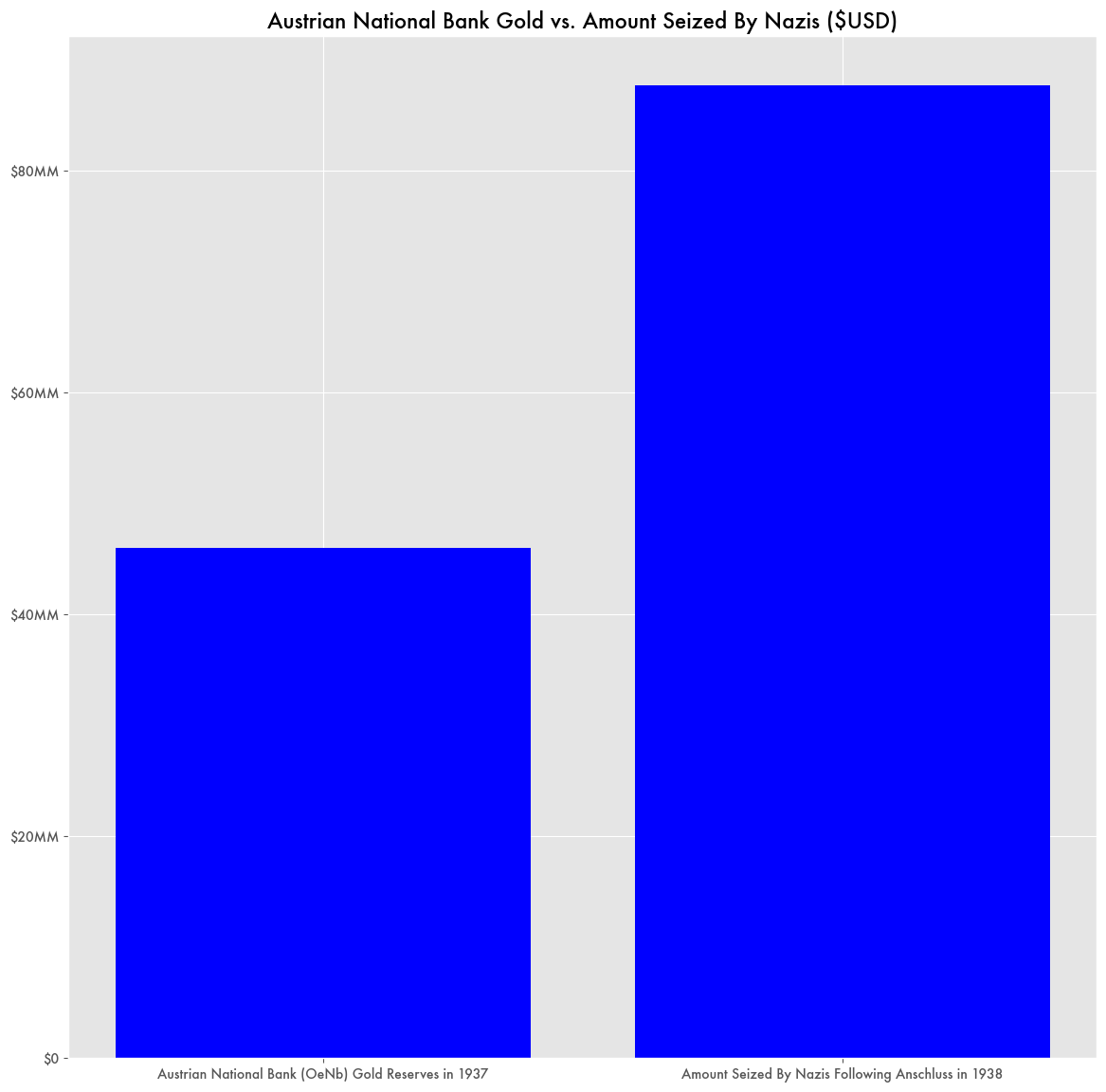

But Austria-Hungary’s debt was largely in the form of war bonds, something that wouldn’t account for large transfers of gold. Some of the collapse in gold reserves may have just been on paper. When the Nazis seized power and invaded Austria with the Anschluss, they confiscated the entire gold and foreign currency reserves of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB)—78,267 kilograms worth—approximately $86 million USD based on a gold value of $34.85 per troy ounce at the time and 32.1507 troy ounces per kilogram.

That was almost twice what the OeNB was reported as holding in gold reserves in 1937—$46 million—and more than the Austrian and Hungarian national banks’ reserves combined, but about the same amount by weight held by the Austro-Hungarian National bank during WWI.

That still wouldn’t account for the approximately 300,000 kilograms of gold that disappeared before the war that left the country mired in debt.

Certainly, Austria’s and Hungary’s economies were in massive flux following the war. Borrowing and printing led to hyperinflation of the Austro-Hungarian krone similar to that of the Deutschmark to the point that Austria’s money supply increased by 14,250 percent between 1919 and 1923.

The League of Nations would jump in to help bail out the country’s finances with a $17 million loan that would ostensibly rise to $150 million. In 1931, Austria would then be hit with a banking crisis when a major lender, Credit-Anstalt, fell into bankruptcy.

But independent of inflation, their debt, or other financial obligations like foreign currency reserves, the amount of gold should be the same unless there was some massive transfer of gold out of the country.

For example, Germany was also in massive debt from WWI. They financed the war through bonds that generated around 97 billion Deutschmarks—around $18 billion USD at the time, pre-hyperinflation. At one point debt constituted 93.8 percent of the country’s gross national product.

Yet, while both countries were heavily indebted, Germany’s gold reserves had barely budged since before the war. Germany still had $287 million worth post-war, not so different from their pre-war accounts of $287 million in 1913.

To help pay off their debts and the heavy reparations demanded by the Treaty of Versailles, Germany’s central bank printed Deutschmarks by the millions to make payments.

Eventually, the Allied powers demanded Germany’s debt be paid in something that couldn’t be massively devalued, such as raw materials like coal and timber. To ensure those payments were made, France occupied Germany’s Ruhr valley, leading to a conflict that helped inspire the Nazi rise to power.