When Voter Registration Metrics Include Non-Citizens

A prior Investigative Economics story highlighted how California’s eligible citizen voting population suddenly jumped from 25 million to 30 million in a single year based on Secretary of State data. That change didn’t happen in other population data sets, like that of the U.S. Census.

But the 30 million number happens to line up with California’s population of the total 18 and over population at the time—not just citizens, but citizens and non-citizens included.

The change makes a difference because the larger number waters down the state’s voter registration rate. An egregiously high registration rate, say over 100 percent that should be technically impossible, might trigger an audit of voter rolls and a purge of inactive voters, similar to what recently happened in Los Angeles County.

And it’s not just California. Data published in a report by the Conservative Partnership Institute (CPI) shows that the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC)—a nonprofit focused on identifying inactive voters—includes non-citizens when calculating their registration rates. It lists the California voting age population at 30 million rather than 25 million along with similar discrepancies for other states.

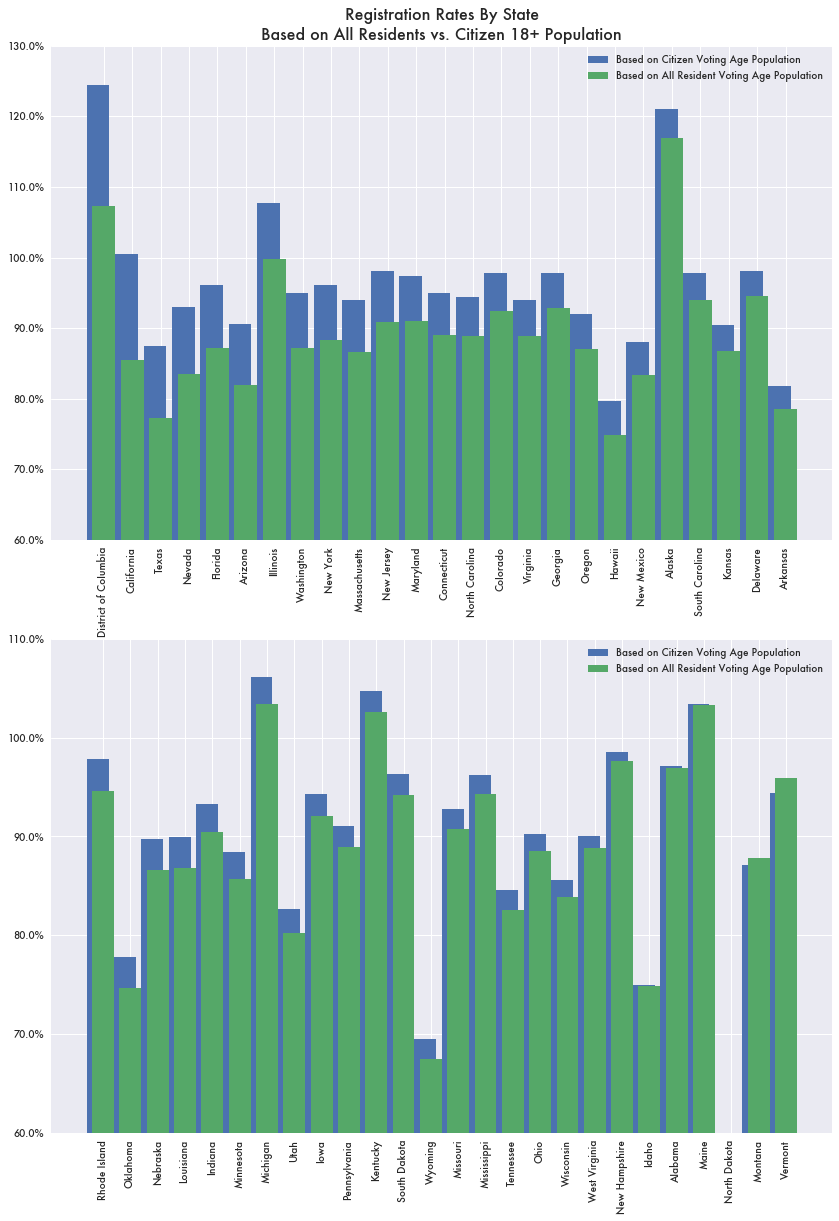

If registration rates used 18+ citizen population from the U.S. Census for eligible voters, the ERIC data would show California’s registration rate at over 100 percent rather than 86 percent. Texas’ rate becomes 88 percent rather than 77 percent. Nevada is 93 percent rather than 84 percent.

ERIC data shows Washington, D.C. with a 107 percent registration rate—something obviously not right. But that rate becomes an even higher 127 percent when excluding non-citizens and factoring in updated population totals from the pandemic. The city lost around 40,000 over-18 residents after 2020 based on Census data.

Currently, no states allow non-citizens to vote. Washington, D.C. recently passed a bill to allow non-citizens to vote, but it is not yet in effect. Not all states have a large discrepancy between the two numbers, like Idaho, where the non-citizen population is small.

Background on ERIC

In 2005, Kansas established the Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck (IVRC) program as an attempt to check voter registrations across states to identify duplicates based only on names and dates of birth. The program was heavily expanded and promoted by Kansas attorney general and prior secretary of state Kris Kobach.

But the program was rife with accuracy issues. It was eventually shut down following a lawsuit from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) over inaccurate matches and potential privacy violations.

In its place would come ERIC. But it too would become divisive and many states would leave the voluntary program accusing it of being partisan—aligning too much with Democrats—having privacy issues, and not being transparent. It was started by David Becker who was previously the director of the left-leaning People for the American Way. CPI accused ERIC of having close ties to Democratically aligned non-profits like the Mark Zuckerburg-funded Fwd.US.

The Sloppiness of Voter Registration Data

Whether ERIC’s analysis is flawed or the underlying data is flawed is hard to determine. Voter registration data is generally fraught with complications. Because much of it involves potentially sensitive, personally identifiable information like social security numbers, the data and the analysis used to determine inactive voters are often not publicly available.

The original data can also be messy or missing depending on the jurisdiction—either because the jurisdiction doesn’t have it or didn’t provide it.

For example, in U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) data for 2020, there are 57 jurisdictions with no data on active voters—53 of which are in North Dakota. California, Hawaii, Kansas, and Maine each have one jurisdiction without active voter data.

Two areas are listed as having less than ten percent of its registered voters being active—which seems improbable—Marshall County, Alabama and Ford County, Illinois.

Massachusetts, Virginia, and Maine have more voters flagged as having moved out of state than are classified as inactive. Over 10 percent of registered voters in Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire have left—the largest proportions of any state.

Vermont has over 44,000 citizens slated as inactive or set for removal from voter rolls, yet there are only 33,000 listed as having cause for removal—e.g. moved, died, or mentally ill.

Vermont, Virginia, Maine, Massachusetts, and Illinois are all ERIC member states. Alabama had been but recently withdrew.