Where Did Greece's Deficit Come From?

The general story behind the Greek financial crisis around 2008-2010 is that the country had secretly been hiding its debt. When this hidden debt was revealed, the country was effectively bankrupt and immediately needed a bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

But the Greek government has pointed the finger at a statistician, Andreas Georgiou, then-president of ELSTAT—the Greek statistical agency—and previous IMF staff member. Greece claimed that Georgiou inflated the country’s statistics so that Greece’s budget deficit was over 15 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), or about €36 billion.

The stark revision forced the country into a bailout with the IMF and the E.U. Private creditors had to sell Greek bonds at a substantial loss, and Greece had to borrow money at a much higher rate as their credit rating had been slashed to junk status. To receive the bailout, Greece had to implement a set of austerity measures—scrapping pay increases and bonuses while raising taxes.

Georgiou was acquitted of charges in 2019, but he was then charged with two other crimes: one for not submitting the statistics to a vote before releasing them and another for slander.

Various editorials have come out to defend Georgiou, pointing to the fact that statistics he compiled were verified and supported by European statistical agencies.

Based on revisions made under Georgieu, a 2010 European Commission report listed the change in the country’s deficit went from 3.7 percent of GDP to 12.5 percent of GDP for 2009, or almost €20 billion. For 2008, it went from 5 percent to 7.7 percent of GDP, or €6.5 billion.

But where did the inflated numbers come from? The European Commission report analyzed Greece’s statistical output and highlighted what it said were “exceptional” methodological lapses. While most revisions were relatively small, there was one for hospital liabilities that was revised by €2.6 billion.

While that was substantial—approximately 1.09 percent of GDP for 2009—it doesn’t come close to €26.5 billion in total revisions. And as liabilities, they wouldn’t affect the deficit, just the country’s debt.

Currency Swaps

Part of the issue is that Greece worked with Goldman Sachs to invest some of the country’s capital in currency swaps—investments in foreign currency—which effectively hid debt in their own currency. The swaps helped Greece enter the E.U. as entrance comes with restriction that member states can’t have substantial debt in their own currency.

The currency swaps have become a lightning rod for blame in the financial crisis. Goldman Sachs defended the deal in 2010 stating that it was a common practice done by other Euro members, that it’s approved by Eurostat guidelines, and that it helped Greece join the Euro zone.

The swaps only changed the country’s deficit-to-GDP ratio by .14 percent and its debt-to-GDP ratio by 1.6 percent in 2001. In total, the swaps reduced the country’s foreign denominated debt on paper by €2.367 billion. A Eurostat report listed the total holdings in debt at over €5 billion.

Substantial, but still not close to €26.5 billion. And like the hospital liabilities, the currency swaps would only affect the country’s debt—what it owes in the future—not the deficit—what it paid or has to pay that year.

Greece’s revisions to its debt as reported for years 2007 to 2009 to account for the currency swaps would send the country’s total net borrowing from €15 billion in 2007 to €36 billion in 2009 based on currency values at the time. While Greece had been adding a little over a billion dollars in debt a year prior to the revisions, the revisions would add an additional €5 billion a year on top of that.

By 2013, Greece’s debt load would quickly return to what it was pre-crisis.

Deficit Was Growing, But Only Since 2006

Independent of the currency swaps, statistical revisions, and total debt, Greece’s deficit was growing fast for other reasons.

An article by the IMF placed the blame at Greece’s growing pension and wage spending.

Pensions and social transfers increased by a whopping 7 percent of GDP from the time of euro adoption to the eve of the crisis, while the public wage bill rose by 3 percent of GDP. This drove the overall fiscal deficit from 4 percent in 2000 to more than 15 percent of GDP in 2009—a staggering five times the Maastricht limit.

While deficit as a percentage of GDP did reach that staggering 15 percent, most of that occurred in the two years preceding the crisis—a few years before that the deficit wasn’t such a big issue. In 2006 the deficit was a paltry 4.6 percent of GDP. Between 2004 and 2006 the deficit was actually declining.

Social Security Spending

While the IMF was right that spending was increasing, it had been increasing for years prior to Greece joining the Eurozone.

Much of that was through social security benefits. With an aging population and inflation, social benefits went from around €10 billion to over €45 billion a year between 1995 and 2009. As a percentage of expenditures, it increased 10 percent.

In 2009, Greece’s deficit topped €33 billion, most of it unrelated to currency swaps or hospital liabilities.

High Spending But Also High Revenue

Greece’s deficit wasn’t increasing because the country was bringing in higher amounts in terms of tax revenue to pay for it. Until the revenue dried up.

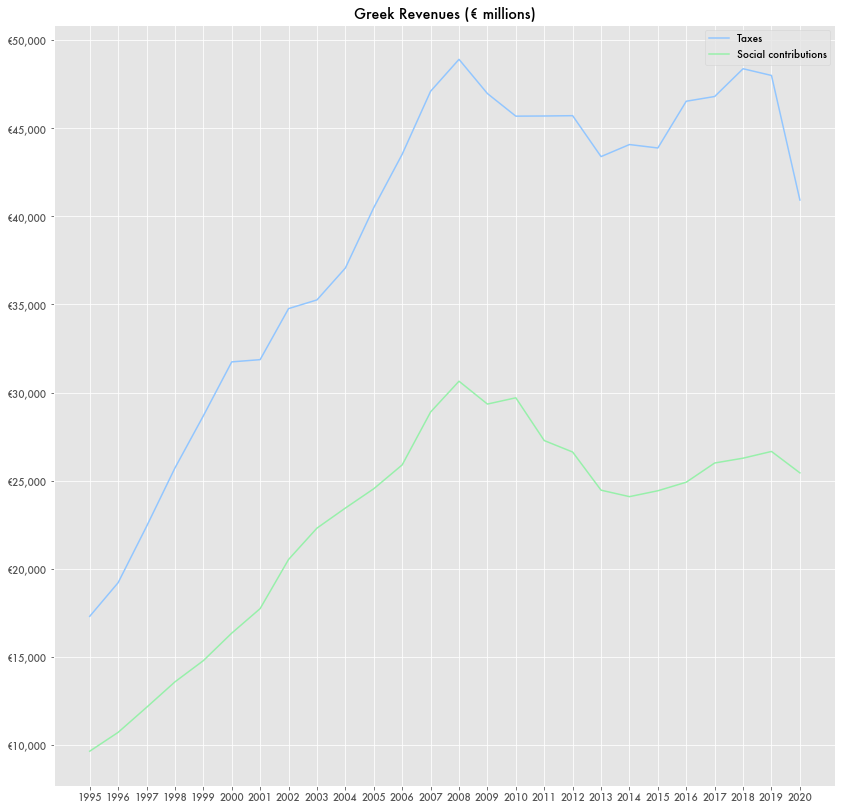

Through 2006, tax revenue and social contributions—effectively payments made to pensions and social security-like programs through employers—continued to rise with government expenditures.

But in 2008 the two diverged drastically. Revenue stopped growing as expenses continued to climb through 2009.

Both sources of revenue—taxes and social contributions—went from a steady ascent to a descent in 2008 creating the large deficit of the Greek crisis.

Accusations of Tax Avoidance

Tax revenue falling during the crisis is ironic since tax avoidance was considered endemic in Greece. It was ranked one of the highest in Europe in terms of “corruption perception” by Transparency International, and the IMF released a report detailing various studies showing that Greece had a large shadow economy. According to the IMF report, while Greece has a high statutory rate, because of tax avoidance the effective rate is much lower than other European countries.

But the Corruption Perception Index is solely based on opinion polling and not related to tax avoidance. The studies in the IMF report were based on estimates.

As a percentage of GDP, Greece actually takes in a fair share, sometimes higher than other major European countries.

At the time of the financial crisis, Greece took in only slightly less in tax revenue than France and much more than Germany. In terms of total revenue including pension payments, it lies somewhere in between the two.

Changes in Tax Law

IMF data doesn’t provide any detail as to why tax income began declining in 2006, but an IMF report gives some detail as to what was occurring around that time. In particular:

During 2004–07, the authorities unified the taxation on interest income, eliminated tax exemption on retained earnings for certain industries, extended the VAT to real estate transactions, and strengthened tax administration by stepping up tax audits and cross verifications. More generally, the emphasis was on reducing direct taxation and increasing indirect taxes.

An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report from 2020 shows that while rates on Valued-Added Tax (VAT)—taxes on goods and services like a sales tax—were increasing during and prior to the crisis, Greece’s VAT revenue ratio was declining and declining even quicker starting in 2008.

While income taxes are determined by the host country, the E.U. requires that the standard VAT rate must be at least 15 percent, and the collected VAT determines how much the member country contributes to the E.U.