Who To Believe On University Administrative Bloat

According to any number of articles, administrative bloat is overwhelming the university system. What was once a small segment of college campus used to handle application paperwork is now a bureaucratic behemoth, handling anything from diversity initiatives to fundraising and government regulations.

Schools like the California Institute of Technology, Duke University, and the University of California at San Diego actually have more non-faculty employees on campus than students as tuition costs have kept going higher and higher. Reports have detailed that “spending on administration per student increased by 61% between 1993 and 2007.” Since then tuition costs have continue to climb with more students chasing debt to get a degree.

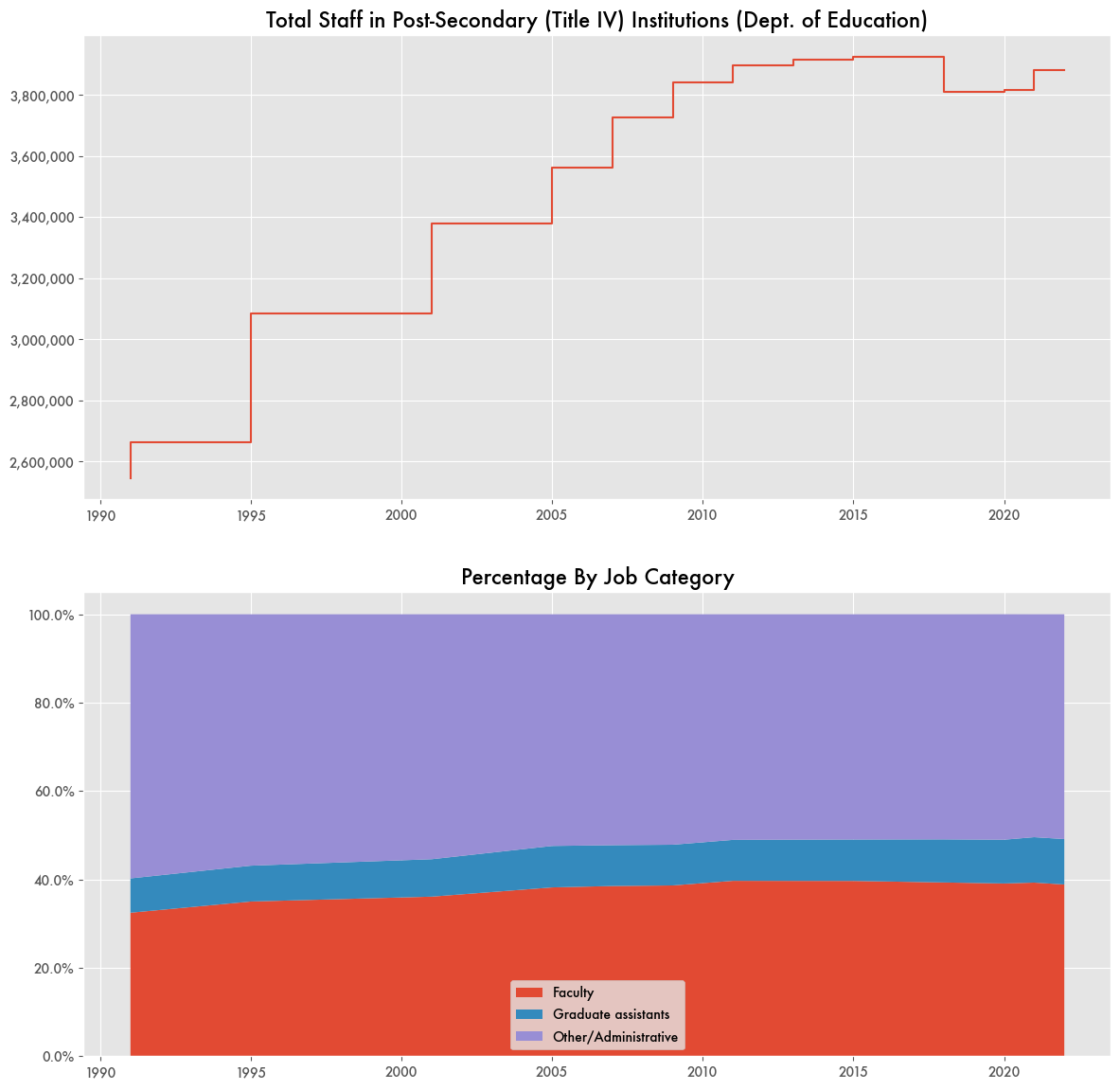

But that was almost 20 years ago. According to the Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data, employee headcounts at universities have actually declined since 2011 as tuition increased.

The NCES data also shows no sign of a tsunami of university administrators. While the total number of administrators grew with the growth of schools prior to 2011, as a percentage of total employment, administrators have actually declined slightly in favor of faculty going back to the 1990s.

Those metrics diverge from every understanding about university spending in the last decade: more tuition, more spending, more administration, more employees.

It also contrasts with some data from the universities themselves who all note increases in total headcounts over that same time period.

Even colleges like the University of California that measure employees in terms of full-time equivalents (FTE)—the number of total hours worked out of the total hours in a year, used to account for part-time faculty—show significant staffing growth over the last decade.

And not just a little. Out of a random selection of the largest American universities, since 2014 employee headcounts grew by 20, 40, or 60 percent according to reports by the universities. For the University of Texas system it was 84 percent, going from 87,000 in 2014 to 160,000 today. University of Wisconsin was one of the few to show a less than 10 percent increase (7.7 percent).

But not all universities show that. For example, Yale annual reports align with the NCES trends showing more spending on faculty, not administrators.

University Hospitals Muddy The Waters

One complication in getting a proper metric for total staff and total administration is that many large scale universities operate teaching hospitals. The hospital’s business is sometimes interwoven with that of the main campus.

For example, Duke University, whose total staff count (27,413) outnumbers their student body count (17,543) for 2024. If you include the Duke University Health System (DUHS), it’s another 30,470 employees.

While Duke University lost about 3,642 employees since 2020, the hospital gained 8,250. Not all schools break down their staff numbers like this in their annual reports.

College Crashes, Mergers, and Acquisitions

Some of those changes can be explained by the large-scale consolidation happening across the university system. The growing cost of tuition has affected smaller colleges with dwindling student bodies, many of whom have since folded or been folded into larger state university systems, leading to more staff at the acquiring institutions.

The federal underwriting of student loans that happened in the 2010s helps subsidize the student loan system that is constantly hemorrhaging cash, but it also established standards for colleges to receive federal aid. For example, the Gainful Employment rule established that if a school’s graduates don’t earn a substantial income after graduating on average, they lose access to Title IV federal student loans and grants.

A lot of those events followed the Law School Crash, wherein numerous programs were found to be graduating thousands of students mired in debt for an advanced law degree only to end up working at McDonalds. Other schools were caught falsifying the graduate employment statistics they provide to the government.

As a result, schools that can’t recruit enough students to pay the high costs of education or receive federal assistance are struggling to survive.

But even if small schools are closing and large universities are getting larger, nationwide there are still more students paying more money and ostensibly there are more staff to handle that growth.

Yet overall, hourly enrollment is declining. While total student headcount varies from year to year, fewer student are attending school in terms of full-time equivalency since 2010.

Schools are still bringing in more and more money—over $150 billion a year more than 10 years ago for public institutions—but providing less in terms of credits per student.